Roses for winter.

Welsh, Edith B.. "Roses for winter." American Homes & Gardens 6, no. 3

(March 1909): 93-94.

[https://library-projects.providence.edu/rosarium/view?docId=tei/rg0156.xml]

One of the sadnesses of the summer garden is the fact that its beauties last for such a short while. Too soon the winter comes, when we may search in vain for the gay blossoms which held up their head so brightly to the warmer sun. But with a little care it is possible to preserve at any rate one of the most valued of our flowers, and in this way retain some of the loveliness of the border for the dull months. In this article a special method of treatment is indicated whereby roses may be dried, and, when required, brought back to a fair resemblance of their original beauty.

The best time to set about this method of preserving roses is in the fall, when, owing to the cool weather, the flowers develop more slowly and are thus in every way better. Almost any of the larger kinds will answer the purpose well, and the blossoms should be gathered when in bud, just after the petal mature and yet before they have started to unroll. Care should be taken to see that the buds are quite dry, and if they should have any moisture on them it is well to spread them out for a day or so in order that the dampness may pass away. As many roses as possible should be secured in order to make allowance for a certain number of failures; it is not to be expected that all will be entirely successful.

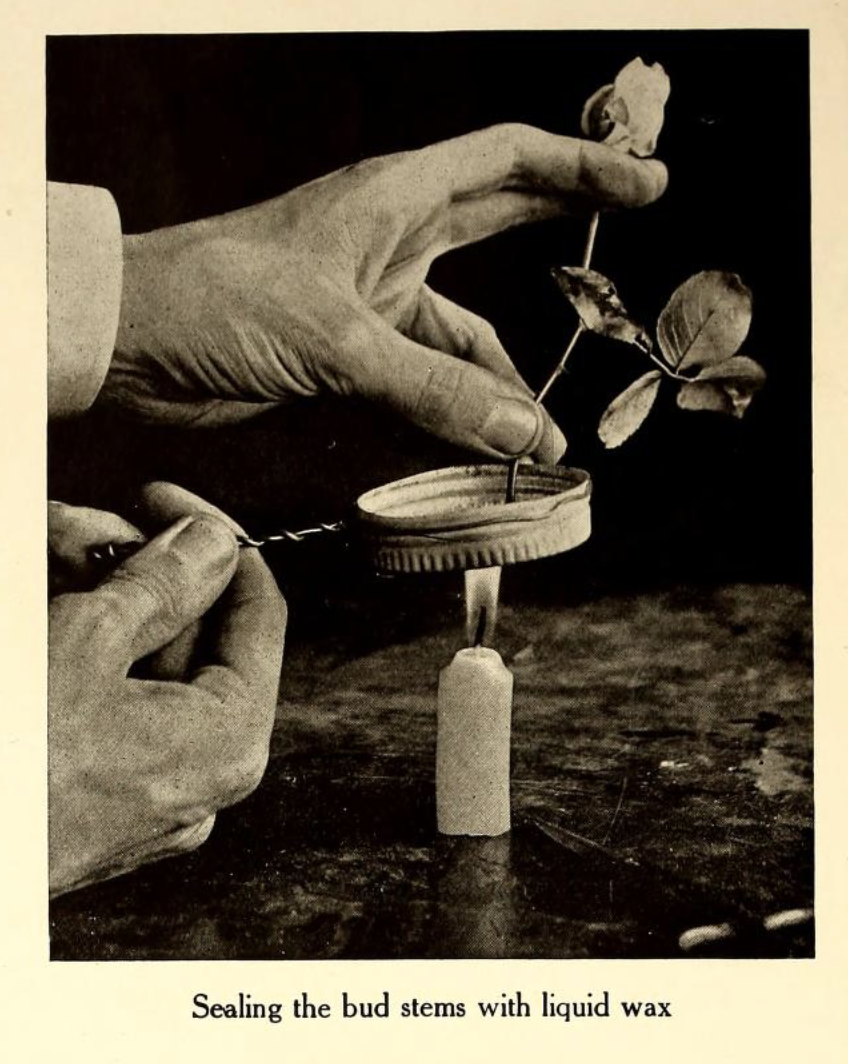

With all the buds to be preserved gathered together, the next step in the treatment may be taken up. Procure the lid of a tin can and round this twist a piece of wire in such a way that it can be held like a small pan. Now into the receptacle place a few lumps of candle wax; then holding the lid over a lighted candle. Take each rose bud and dip the end of the stalk in the melted wax, repeating the process several times so that a small lump of the substance is formed on the end of the stem. Next, very carefully tie a small piece of silk twine round each of the buds—jus tightly enough to keep in place without in any way injuring the petals.

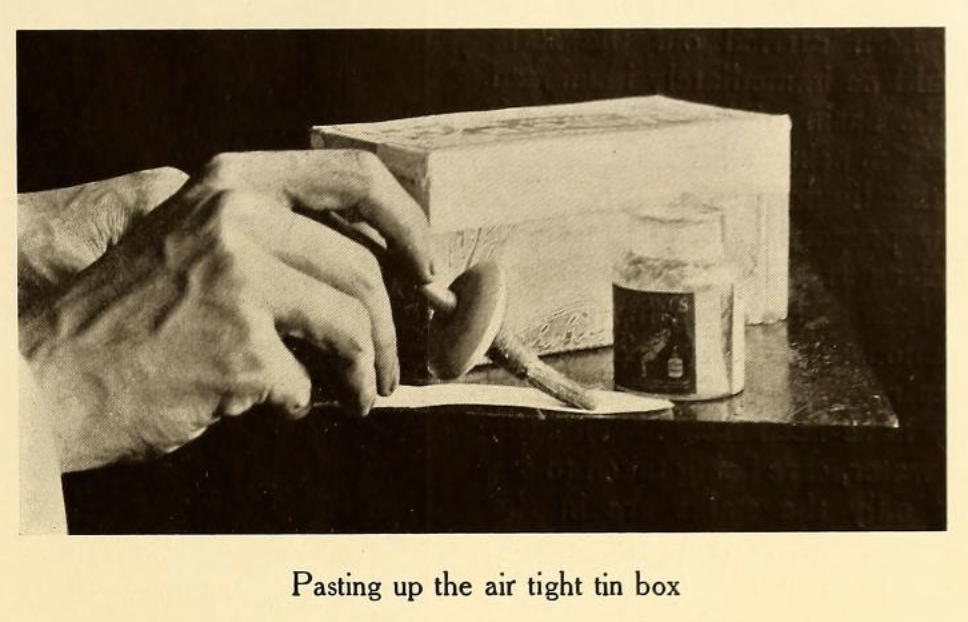

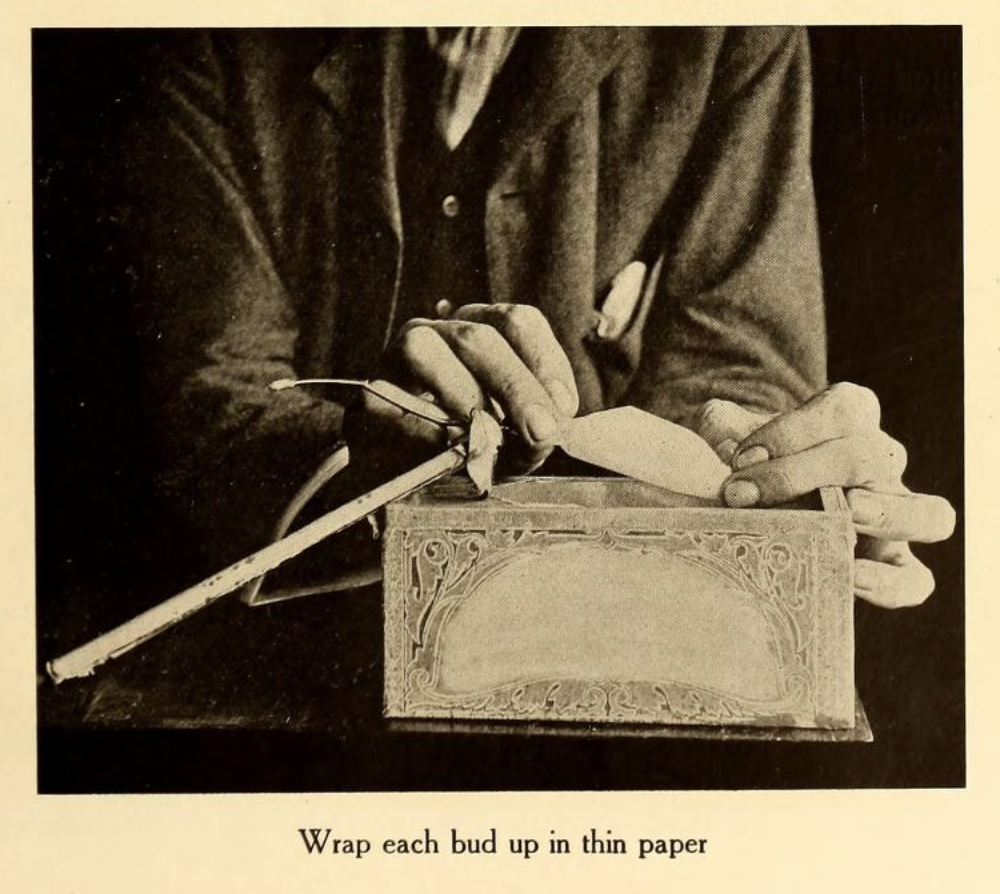

The next thing required will be one or more tin boxes. It is not recommended that these should be very large, those answering the purpose perhaps best of all being the small long-shaped biscuit boxes. The lids of these, as a rule, fit exceptionally well, and this is rather an important feature. Take some tissue paper and cut this into pieces each one of a size to accommodate a single rose bud. Wrap the flower head of each specimen in the paper, tying it securely at either end with silk. It may be as well here, perhaps, to insist again on the importance of each rose being absolutely free from any surface moisture, one example in a damp condition placed in a box being sufficient to spoil the whole of the contents. When the roses are wrapped up they may be packed away in the boxes, each of which has been previously lined with wadding. The buds may be put in fairly closely, as long as they are not really crushed when the lid is put on. In order to make the box doubly air tight it is well to paste thin strips of paper round the joints of the lid. All the boxes as they are loaded with buds should be placed in a closet; it is important that the temperature should be maintained, although the boxes must not be put in a really hot place.

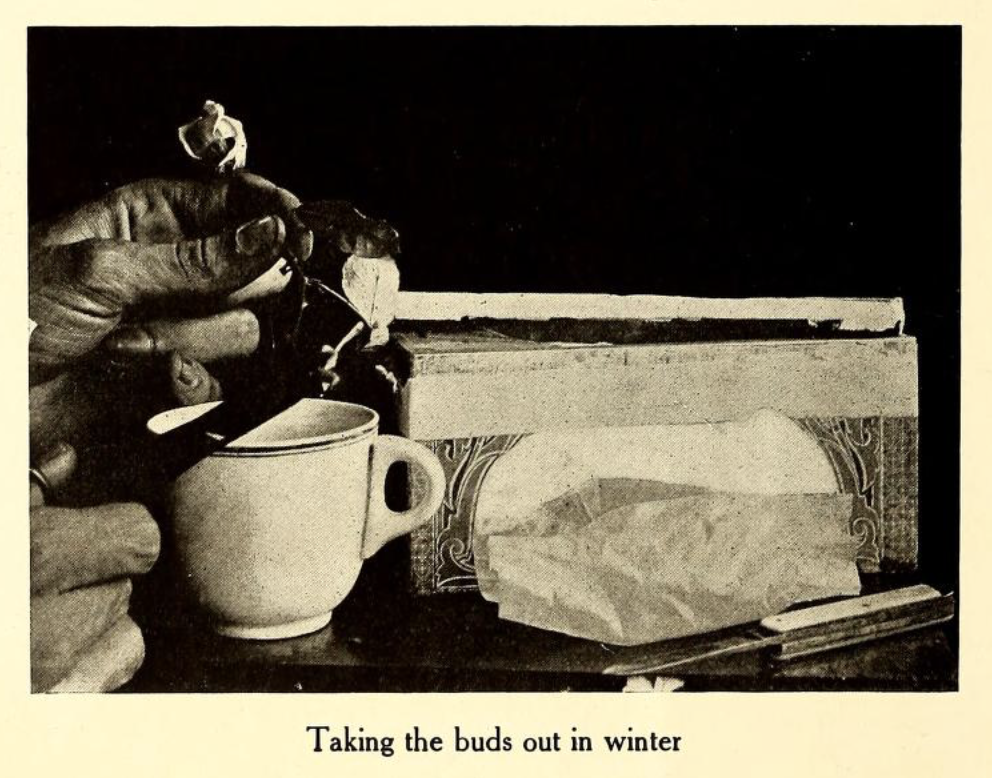

The roses may now be left just as they are for a period of two or three months; longer that this it is scarcely advisable to leave the buds. When it is decided to revive the sleeping flowers the boxes may be opened and the buds taken out one by one. Extreme care must now be exercised in the handling of the specimens, as they will be in a very brittle state, and it is very easy to damage them in this condition. Gently unwrap each bud, and with a small pair of scissors cut away the silken bands which encircle the petals. Next take a basin full of hot—not boiling—water. Now take each bud and with a stout pair of scissors make a clean cut through the stalk a fraction of an inch above the sealed end. As soon as this has been carried out the stalk should be immediately immersed in the basin of hot water, each specimen being allowed to remain in the liquid for five minutes. Now prepare a large bowl full of clean fresh water into which has been cast a small handful of common salt. Into this all the roses may be placed as soon as they have been treated with the hot water, care being taken to see that only the stalks are in the fluid. Now convey the whole thing to a perfectly dark and rather warm cupboard, where the awakening flower should be allowed to stay for several hours. At the end of this time, if the experiment has been carried through on the proper lines, it will be observed that the roses are beginning to take on much of their former loveliness, and in a short while they will develop into much of their original beauty.

Of course, a proportion are bound to be failures, no matter how carefully the roses may have been selected in the first instance. Still with moderate success the worker will feel amply repaid for any trouble taken on account of the value which roses assume in the depths of winter. The treatment might be employed at any time of the year, when roses were available for the purpose.

Like many household arts this simple experiment should not be undertaken without a very ample preparedness for failure. I have already pointed this out more than once, and while I do not wish to discourage those who may be interested enough in this process to undertake it, it is but fair that a further word of caution should be added.

One should not, however be altogether deterred from the possibility of failure from making the attempt. The process is simple enough, and calls for no complexity of apparatus. Nor, indeed, need one go beyond the resources of the ordinary household for the necessary materials. This in itself is one of the charms of the experiment. It is something every one may do and do easily and quite without expense. Moreover, if but a few of the roses survive the period of repose and experimentation, a few will yield sufficient compensation, not only through the novelty of their unusual blooming, but through the sense of satisfaction that one will feel that so simple and so beautiful an experiment should have yielded some result.

Perhaps it is difficult thing to have too many roses in summer; one fairly longs and yearns for the blooming time to hasten, once it seems about to arrive. But one cannot have this royal flower in the winter season without great expense, and then not always in a satisfactory way. The plan here outlined offers delightful opportunities of rose-enjoyment at a time of year when roses are not only scarce, but are positively unknown in the ordinary house. And they will be real roses too, but strangely artificial ones that are sometimes offered to the enjoyment of the rose lover, who, however, knows but the real flowers and can have no patience with the most skilful imitation.