Quest of the perfect rose.

Clarkin, Franklin. "Quest of the perfect rose." Everbodys Magazine 24, no. 6

(June 1911): 746-757.

[https://library-projects.providence.edu/rosarium/view?docId=tei/rg0047.xml]

There it stood on its almost thornless stalk—what the minds of rose-growers had dwelt on as the end, the limit, the Ultima Thule, terminating half a century of devoted experiment in innumerable greenhouses and gardens throughout the world: The Blue Rose!

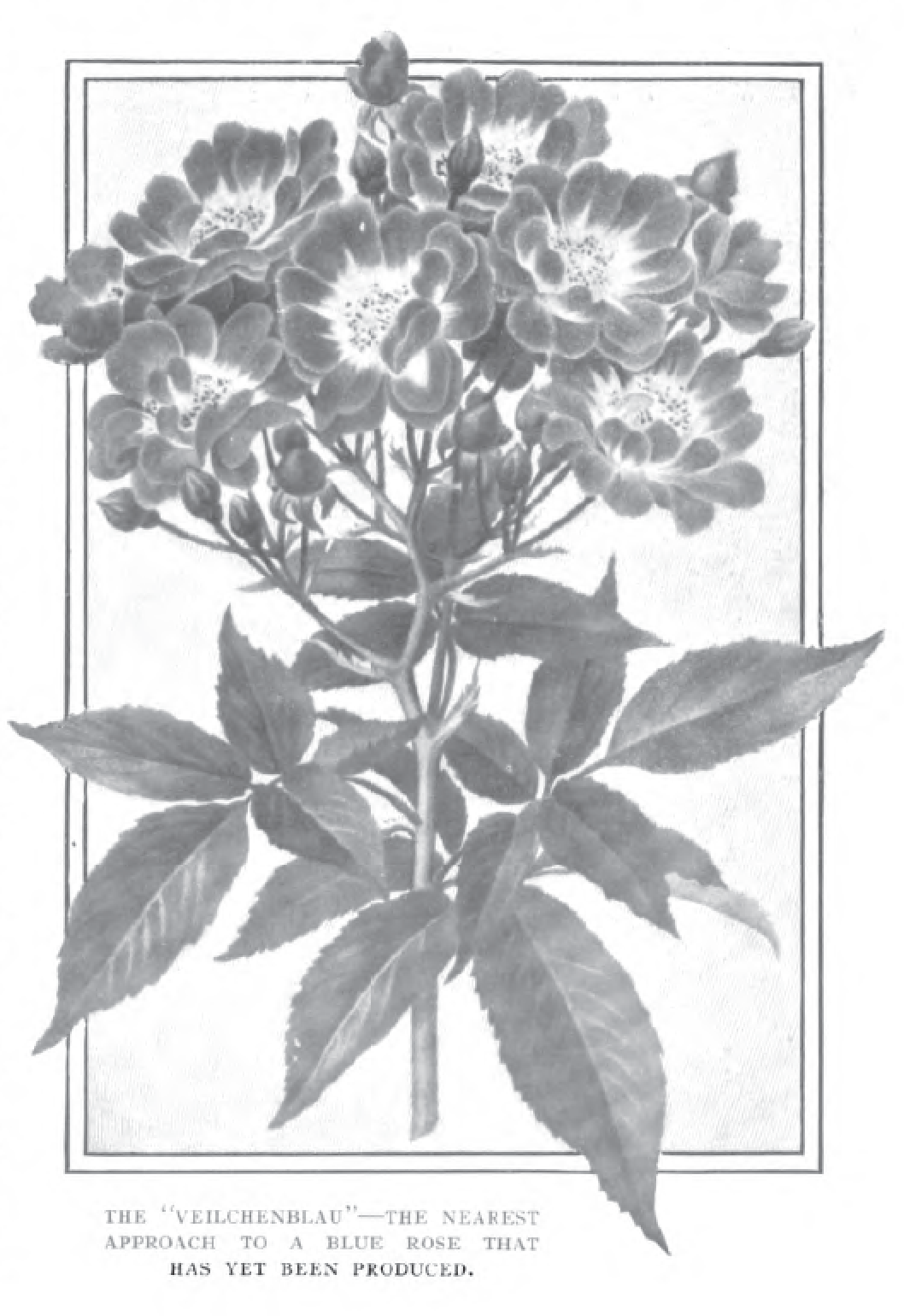

Its tag said: "Allerneueste Schlingrose ‘Veilchenblau,’ J. C. Schmidt, Erfurt."

Made in Germany—the supreme achievement so far in breeding the national flower of England, made in Germany!

My friend the rosarian had been intensely curious about Herr Schmidt’s wondrous production. Here it was, in bloom, stout as a young tree, blossoms clustered as formally and gracelessly together as an old-fashioned nosegay.

He was silent before it. But you know of the bitter jealousies, contests, imprisonments, persecutions, political tragedies, which attended the production of a black tulip when Holland was crazed over tulips? Then you will understand. Some one had originated a blue rose, the despair of years, and I imagined my friend saying over and over to himself with agonies of hopelessness: "What’s the good of anything?"

He had been trying with exhaustless patience for new roses. Some had been effected. He had planned and plotted and prepared till three or four times he had treated the world to surprises which would be thundered in italics down through the selectest catalogues. But he had produced no blue rose…

You think of this age as the age of materialism. It is the same age that occupied itself with developing the rose.

Well within a century Byron wrote, "As soon seek roses in December" as "constancy in wind, belief in women," and other acknowledged marvels. We have gained roses in December. Despite old Omar, spring no longer "vanishes with the rose," or it would never vanish. Breeders multiplied petals; they have varied colors and shades till color-nomenclature has been virtually exhausted; given climbing habits to staid, long-stalked, majestic forms; brought scent to the scentless; negatived the saying that "there’s no rose without its thorn" ; conquered the seasons by inducing "perpetual" blooming.

Miracles have been wrought year after year, yet two achievements remained beyond the efforts of the hybridizers who were laboring in their glass houses with the patience of medieval chemists. These elusive things are:

The Blue Rose.

The Perfect Rose.

If they could get the one, they could get the other. This double purpose, one of the fascinating, beyond-the-horizon quests, engaging the imagination of generations of rose-growers, has driven them to enormously expensive and prodigiously patient trials.

Not for profit have they striven—as in the efforts to gain Nature’s secret formula for making gold or diamonds. Nor for the satisfaction of rousing elemental instincts, as in orchid-hunting, which appeals to hardihood, daringness, the joy of testing one’s self against unseen perils. Rather, the lure for the rosarian has been the quiet enchantment of the magics of science—the same which impels highly studious minds to adventure into the mysteries of how Nature carries on creation in her occult laboratories—and to go her one better.

My friend had been continually laying a train, hoping for a flash that would turn out a classic illumination. I was to learn that rose-breeders and hybridists have "the true soul of Adam in them." They may be so supernally sensitive about roses that they will pile labor on labor to remove some fancied taint in the gold of a yellow, and even "get chilblains from merely looking at a snowdrop" ; yet they will brave any sloughs of despond in chase of that will-o’-the-wisp, perfection.

"Why should any one want a blue rose, anyway?" I asked, by way of easing off his seeming disappointment. "Who cares for the green carnation? Doubtless science could make a violet of any deviation of color to be seen in the spectrum. But doubtless science would have its labor for its pains—as it would if it made an unsweetened sugar."

His answer came, with no discouraged tone in it:

"Of course there’s nothing beautiful about a blue rose. The effort for it is simply one of those strivings for the always-desired—for the impossible."

He called it the "impossible" —yet was not the attainment here? He made me wait for an answer to the riddle, while he talked of roses and rose culture.

There are florists who maintain that a rose of true blue, of legitimate growth, which will reproduce its kind, is neither naturally nor scientifically feasible.

"In spite of legends, traveler’s tales, and catalogue announcements, the law governing the colors of flowers renders blue roses an iridescent dream," declared the rosarian. "Blue, yellow, and red are never seen in the same species of flowers."

"Any two of them may appear, but never three. There are red and yellow roses, but never blue; there are blue and yellow pansies, but never red; there are red and blue verbenas, but not any yellow."

"Besides, in all floras blue is rare, as are blonds among human beings. In Europe there are found 1194 white flowers, 951 yellow, 823 red, and 594 blue. There are 308 violet-blues, so-called, sometimes carelessly regarded as blues."

"All tales of blue roses have been fanciful, including the ‘blue rose of the Moors.’ Chemicals will make them to order—like the green carnation; but chemical agencies applied to the root render them, like the mule or the mulatto, impotent. There are bounds fixed."

One instance of a chemical blue rose was that of a Tartar khan who demanded a blue rose or his gardener’s head. Out of the consternation there was born, so he was told, the issue he required. It pleased him to think that despotism could so splendidly coerce advancement—as many rulers have fancied since. But when that gardener died, not another blue rose was to be had from the wondrous bush which had been bearing them year after year. Nor would its slips or seeds bring forth blooms of the desired color—which is what a rose-bush must do to perpetuate a new variety.

Nowadays all gardeners know that by inserting a strong blue pigment under the pellicle that covers the roots, binding them in oil, and sprinkling well with indigo water, new shades will come. That has been known since the Middle Ages.

The first good roses arrived in the Occident during the Crusades. By the delicate hand of Peter the Hermit, who preached the Crusades? No. By the mailed fists of those boldly chivalrous spirits who cut a swath to the East to search for and protect the Holy Grail.

The redoubtable crusading Thibault, Comte de Brie, took pains (more than carrying a lance) of bringing from Damascus a rose, and planting it is Provence, France.

In this place the second son of Henry III. of England found it growing. He carried it home, took it for his device, became the first Earl of Lancaster. Thereafter rival claimants to the English throne adopted the rose as their emblem.

There were wars—Red Rose of Lancaster against White Rose of York—and they never ended till Henry VII. of the Red took Elizabeth of the White as consort. Then, to indicate that the "Wars of the Roses" were over, the adherence of those of the White of York to the Red of Lancaster was to be attested by the payment to the throne annually of a white rose. Thus what the Crusaders brought back from Damascus became the tutelary flower of England, soon symbolizing its vigor, its full-blooded dominance.

Further solemnly certifying the union, in the next century came the Rose of York and Lancaster—striped red and white—as long as roses blow the symbol of that peace.

The English oak, the English yew, the English rose—there you have the qualities of the Englishman set forth by a form of elective affinity; his staunchness, the droop of melancholy to his spirits, his susceptibility to sentiment, which led Chesterton to call the English one of the emotional races. Everywhere in England the rose received affectionate and proud nurture. Above the humblest cottage threshold it was made to clamber. It served in kings’ gardens and queens’ palaces. Often it was used as the most delicate of delicate considerations; as when the Bishop of Ely leased Ely House to Queen Elizabeth’s Lord Chancellor, and stipulated only that a "red rose be paid for it on Midsummer’s Day."

William Penn, turned out of doors because he would not be compelled to doff his hat to a king, brought the sentiment to America. In the colony he founded, he granted land for a tavern at Bethlehem to be known as The Rose; the yearly requital simply one red rose.

Rose Tavern itself and the roses have disappeared from sight under the belching chimneys of Schwab’s immense steel works; for one thing a rose can not endure is smoke. But until the state of Pennsylvania bought up all the tremendous proprietary rights of Penn’s heirs for $500,000, no other rent was accepted. Then the compensation was changed to hard coin.

But the custom survives, and if you entered the Pennsylvania town of Manheim on the second Sunday in June, you would witness one of the prettiest spectacles of the times—the ceremony of the payment, by the Zion Lutheran Church, of one red rose for the land Baron Steigel gave to the congregation two centuries ago.

He had come to the colony seeking greater fame, fortune and liberty. He married the daughter of Huber, the ironmaster, bought his foundry; set up also the first great glass factory. Sundays he taught a Bible class in his mansion; then gave to the people land for a church.

He gave it with these words in the deed:

Yielding and paying therefor unto the said Henry William Steigel, and his heirs or assigns, at the said town of Manheim, in the month of June, forever hereafter, the rent of One Red Rose, if the same shall be lawfully demanded.

There is nowadays a liturgical service attended by all the countryside. The governor of Pennsylvania comes with his gold-laced staff and makes an address; there are sermons, a distribution of roses to the sick; then with solemn pageantry, out of the millions grown in the village, one red rose is paid to Baron Steigel’s descendant, Miss Martha Horning of Newport, Rhode Island.

To deserve the title "rosarian" one must be oneself a high type of development. Otherwise, the graces of character which gardening gives will succumb to pride and vainglory. The causes lie in the power that the work puts in the rosarian’s hands.

Hybridization is intermixing wild natural species, or crossing hybrids already produced. In either case, the method is the same—enormously careful transference by hand of the pollen of one kind of rose to another. Thus:

Enclosed by the petals are hollow tubes called pistils, in the bottom of which are unfertilized seeds or ovules. Bending toward the tips of the pistils are the stamens, on the points of which are borne little sacs, called anthers, where the pollen, the fertilizing element, is formed. Left to themselves, the stamens will shake the pollen from their anthers on to the apex of the pistil, through which it reaches the ovule and fertilizes it.

If you wish to breed together two different sorts, you must first snip off the anthers of one flower, thereby making it solely feminine, instead of double-sexed. This putative mother-flower is them to have its pistils dusted by the pollen taken with a soft brush from the anthers of the flower selected to be the father.

If the day be bright, with plenty of electricity in the air to make all life lively, and if pollen and pistils are ripe and ready, and if the chosen plants are not too remotely different and antipathetic, and if you cautiously protect the flower from insects and winds by tying a bag over it, why, then, D. V., the seeds will form. And if you plant them carefully, about two per cent. of them will spring up and bloom, and you will have produced perhaps a new marvel of creation—or perhaps an unconscionably ugly mongrel!

Such is the innocent magic that often gives a perilous pride to the inventive rosarian. I have it from good authority that if he be at this hybridizing long enough, he runs the risk of losing his humility. To him sooner than to others "a primrose by a river’s brim" ceases to be a primrose, becoming "a mere aggregate of possible points for the next show," which he himself may excel by an artificial loveliness of his own devising. The state of mind he thus drifts into, that of a competitor with the source of life, leads to what Dean Farrar called "moral esthesia and damnation."

If there is anything in heredity, it explains Jackson Dawson, of the Arnold Arboretum, at Harvard University, and why he is among the foremost of rose hybridizers.

Born in a gardening family, he came from England when a child. What was to be his future in the new country was settled offhand one day when his mother found that he had stained most of her books by pressing flowers in them. He was packed off to his uncle, a nurseryman at Andover. Before he became of age, he was well known to florists, and the then celebrated "Hovey’s" at Cambridge took him up. War came on; he interrupted his career to join the Federal army. After three years he returned with two honorable wounds.

Still "hardy" and "perpetual" he seems at seventy, when you come upon him in the yard of the small white cottage in which he has dwelt forty years, just outside a corner of Harvard’s tree-reservation: hale, husky, wide-shouldered, deep-chested, eyes like those of youth, skin tanned by sun and rain but scarcely lined, the calmness of his life giving cheer and pleasant character to his face, and in his walk only a hesitant limp as a reminder of the splintering shot he got in the leg forty-seven years ago.

When Dawson received, as his nineteenth medal, the George Robert White medal of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, Professor Sargent, of the Arboretum, gave this view of him:

"Dawson seems to be able to look at a plant and tell you what its affinities are. He is a wizard. He seems to know the art of grafting by intuition—what stock to use, in what condition to use it, and how to use it. His intuition has been strengthened by patient practice and by loving the things with which he works. Plants seem to respond to affection."

When you glance over the "works" possessed by others, it astounds you to see that Mr. Dawson’s laboratory is just a small room in the cottage, opening upon the ordinary New England back yard—a plot, say, sixty by one hundred feet.

Here is where he had his dismal, innumerable defeats and his brilliant, celebrated victories.

"Tell about the failures," he was urged; for dealing with the inexplicable caprices of Nature has left at least this rosarian humbly chastened in spirit.

"Failures? Why, this business is one blessed failure after another—I couldn’t count ‘em. We don’t know what cells or what conditions change a breed. We only know some general principles of nature."

"I went at rose-breeding as other men go at horse-breeding. If you want to combine certain qualities, you cross those that have them. But there may be the faintest taint in the blood of one of the parents. Then it’s like a white man’s marrying unknowingly an octoroon: The first issue may be white, but the second may be black."

"Flowers skip generations; sometimes comes a reversal to type. This is why hybridizing is full of the unexpected. I’ve been twenty years at this byplay, and what have I brought out? Five or six good roses."

By calling his rose-breeding "byplay" he meant that his real occupation is growing trees and shrubs for the Arboretum—the most remarkable park of varied trees anywhere. Trees now sixty feet high Mr. Dawson himself raised from seedlings collected in forests, or from seed obtained from the farthest corners of the earth.

His problem in roses was to produce a rambler or climber, with color, that would endure the blustering east winds of New England; that would bloom in late fall or early spring.

"First," he went on, "I took the ‘Wichuraiana,’which I had just introduced from Japan, and crossed it with the Chinese ‘Multiflora.’ Both wild, both trailers or climbers, neither feared any sane or reasonable climate, but both were white. I started to put color into them. I couldn’t make a break from the originals for years. Then came a pink bloom. After many experiments I induced this to mate with the scarlet-crimson hybrid perpetual— ‘Général Jacqueminot.’ At last, after numerous seedlings, there came the ‘Dawson.’ This remains the earliest and hardiest of this clan of roses and is widely popular in England."

"How is color put into a rose—how would you go to work to make one blue? By chemicals?"

"Not by chemicals! You don’t use chemicals, do you to cross a Jersey cow with a brindle, or if you cross a razor-backed hog with a Suffolk? You just wait and trust to Fate; and you get what you get. A dyed plant won’t reproduce its dyes any more than a painted donkey will bring forth a zebra."

"Many real hybrids are ‘mulish’ barren. I crossed a red ‘Dawson’ with the white, vigorous hybrid perpetual ‘Madame Luizet.’ Strange to say, the result was a half-climbing plant bearing large single white flowers. It was infertile; would never bear seeds. So with crossing ‘Wichuraiana’ by ‘Jacqueminot’—result very pretty, but lacking the power to continue itself; and the same occurred by crossing ‘Wichuraiana’ with ‘Belle Siebricht,’ a tea; the lovely offspring was salmon, but tender, and ended there."

"‘Crimson Rambler’ is a famous multiflora parent, so I tried it with ‘Dawson.’ That lately yielded one plant of deep old-rose blooms borne in clusters. When I joined the Austrian brier ’Harrison,’ raised in America from seed, with ‘Dawson,’ hoping for a yellow, the offspring were mongrels of the worst sort."

He keeps his pedigrees carefully. The "family-trees" he sets forth in this way:

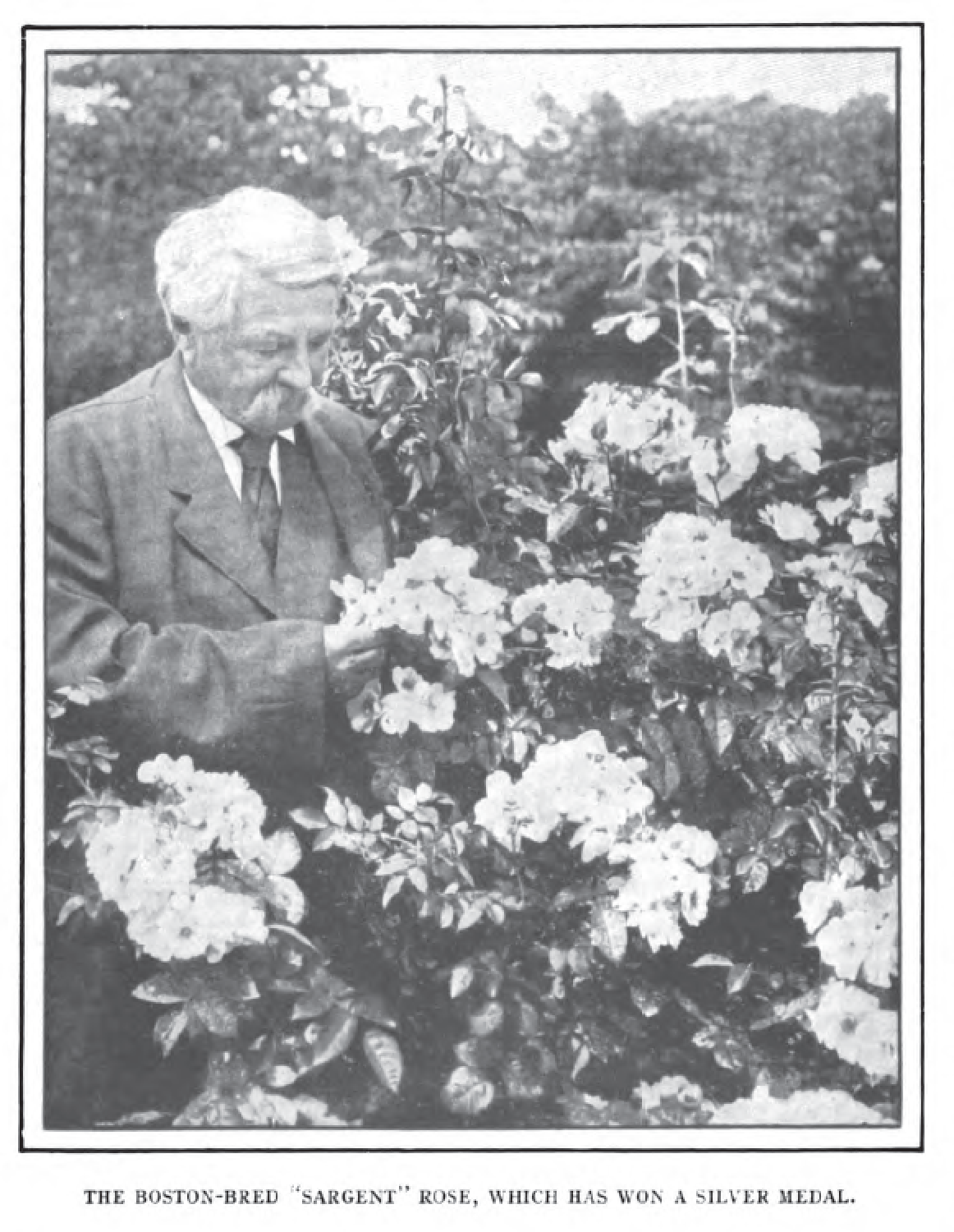

"Wichuraiana" X "Crimson Rambler" ; progeny X "Baroness Rothschild" = "Sargent" rose.

"Multiflora" X "Dawson" = "Minnie Dawson."

"Crimson Rambler" X "Wichuraiana" = "Farquhar."

"Wichuraiana" X "Jacqueminot" = "William Egan."

"Rugosa" X "Jacqueminot" = "Arnold."

"Dawson" X "Wichuraiana" = "Daybreak"

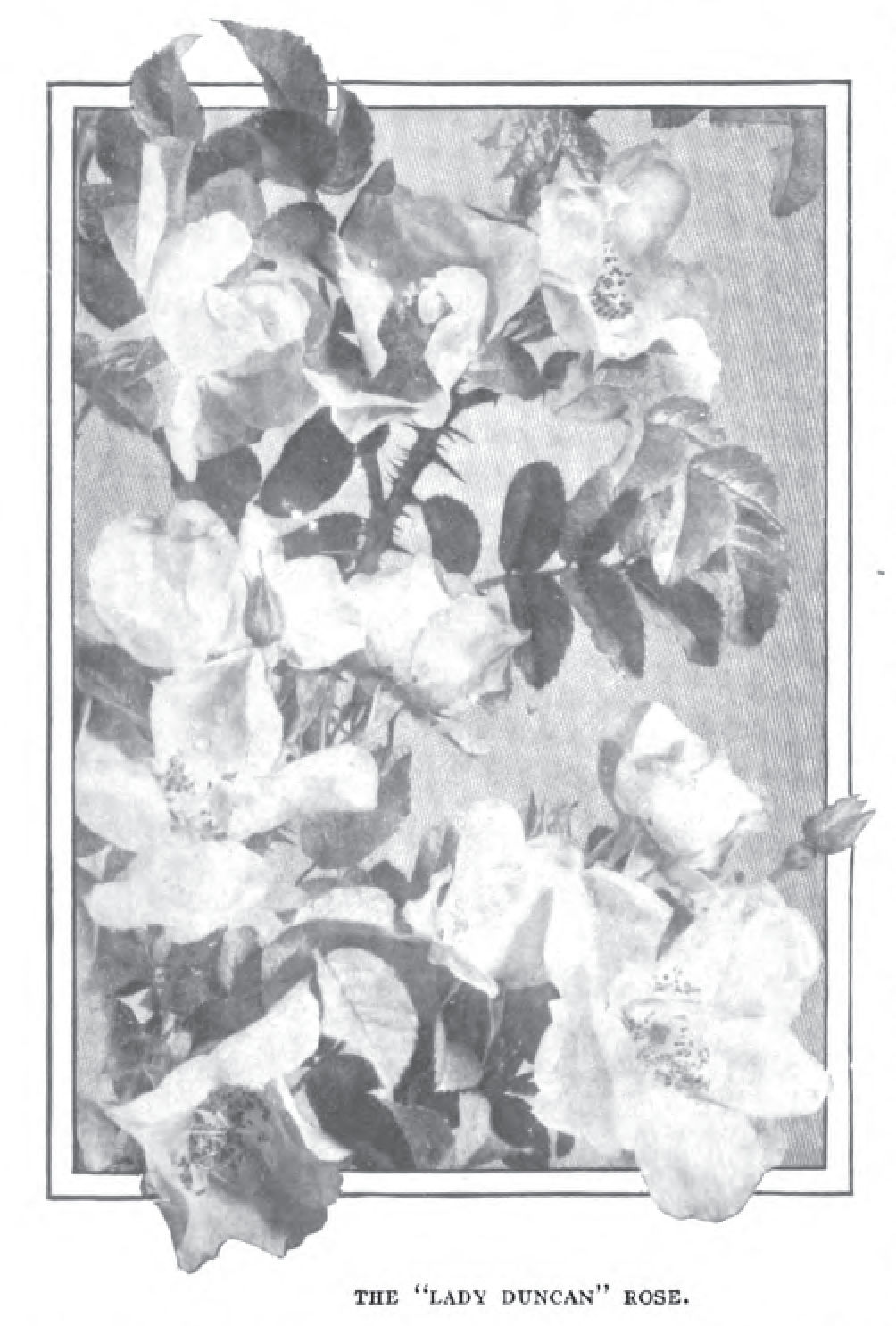

"Rugosa" X "Wichuraiana" = "Lady Duncan."

Because it is the hard-nerved, hard-headed, sometimes hard-hearted persons who have most appreciated that most fragile of flowers, the orchid, I suppose it would be small wonder if the more cloistered and shut-in and introspective should be the ones to take the chiefest delight in the sturdier, more flamboyant rose.

It does not so happen. In this country, besides Baron Steigel, the glass and iron manufacturer, and William Penn, there have been, or are, such men as these among American rosarians: Francis Parkman, who explored the North American wilderness; George Bancroft, historian; Admiral Aaron Ward, in command of the Dreadnought Utah; H. O. Havemeyer, T. A. Havemeyer, of the Sugar Trust; Senator H. A. Dupont, of the Powder Trust; Colonel William Barbour, thread spinner; George B. Post, architect of skyscrapers; Colonel Herbert L. Camp; Spencer Trask, the banker, whose rose-garden at Saratoga may become a park; H. B. Plant, builder of the Florida West-Shore railway.

For Bancroft’s services in rose-culture a variety of rose was named for him— "The Honorable George Bancroft," produced by Bennett in 1879 by crossing "Madame de St. Joseph" with the namesake of another historian, "Lord Macaulay."

Admiral Ward’s garden at Roslyn, Long Island, is known everywhere for its tea roses.

I have said that the pursuit of the rose is less physically perilous than the pursuit of the orchid. The exception is when it is not only the growing and the hybridizing that occupy one, but also the gathering. In the Arboretum the purpose is, under the direction of Professor Charles Sprague Sargent, to assemble from all the ends of the earth plants which will thrive in the climate of eastern Massachusetts.

For five years the Arboretum has had two explorers in the hinterland of China, getting seeds of trees and shrubs and flowers. Some traveler’s tale mentioned that there was in this region a mountain, called the Mountain of the Moutan, "covered with a much-desired wild peony." William Purdom, an Arboretum explorer, was commissioned to find that mountain and send back that peony. E. H. Wilson, another staff explorer, was handed a list of trees and plants likely to thrive in northern United States, among them several roses, and told to seek them over toward Tibet, among primeval forests, and on the slopes of peaks in an untraveled country.

Wilson chartered a junk, went a thousand miles up the Yang-tse River, was hauled through gorges by gangs of coolies, through rapids and fierce contrary currents; trudged afoot to Sachien-lu, the gate to Tibet, "crossing," he wrote back, "through passes of 10,000, 14,650, and 15,000 feet, where we had to hew our path; wading wild torrents; sleeping in the forest under spruce boughs; climbing mountains up to the Forbidden Land."

On this frontier, he was caught in a landslide. His days as an explorer were thus ended; at this writing he is in San Francisco on his way home. What he suffered was written to his friend, Lauriston Bullard:

One leg was badly broken; both bones were fractured above the ankle. Crude splints were improvised, and he was carried to Chengtu, spending two nights at Chinese inns on the way. A medical missionary set the bones. Three days had elapsed since the accident, the leg had swollen greatly, and blood-poisoning had set in. For four weeks the leg was not out of splints. Amputation was narrowly missed, and Mr. Wilson was laid up four months.

He had already sent back an immense number of new rose seeds.

"Many are of strange, unknown genera, and we don;t yet know just how to class them," declared Mr. Dawson, to whose ingenious hands the raising of the seeds has been entrusted.

One of the bon mots of the late Bishop Potter was that "actresses will happen in the best regulated families." So may gardeners. Lord Penzance was an eminent English counselor. During a score of years he had used his skill to put into effect the law decreeing the separation of unhappy human couples. Unlike Dawson, he had shown no early proclivity toward plants. Perhaps it was an untraced strain in his blood; perhaps, and more likely, it was a sudden balking at his occupation that drove him, in the last years of his life, to devote himself to the happy marriage of roses.

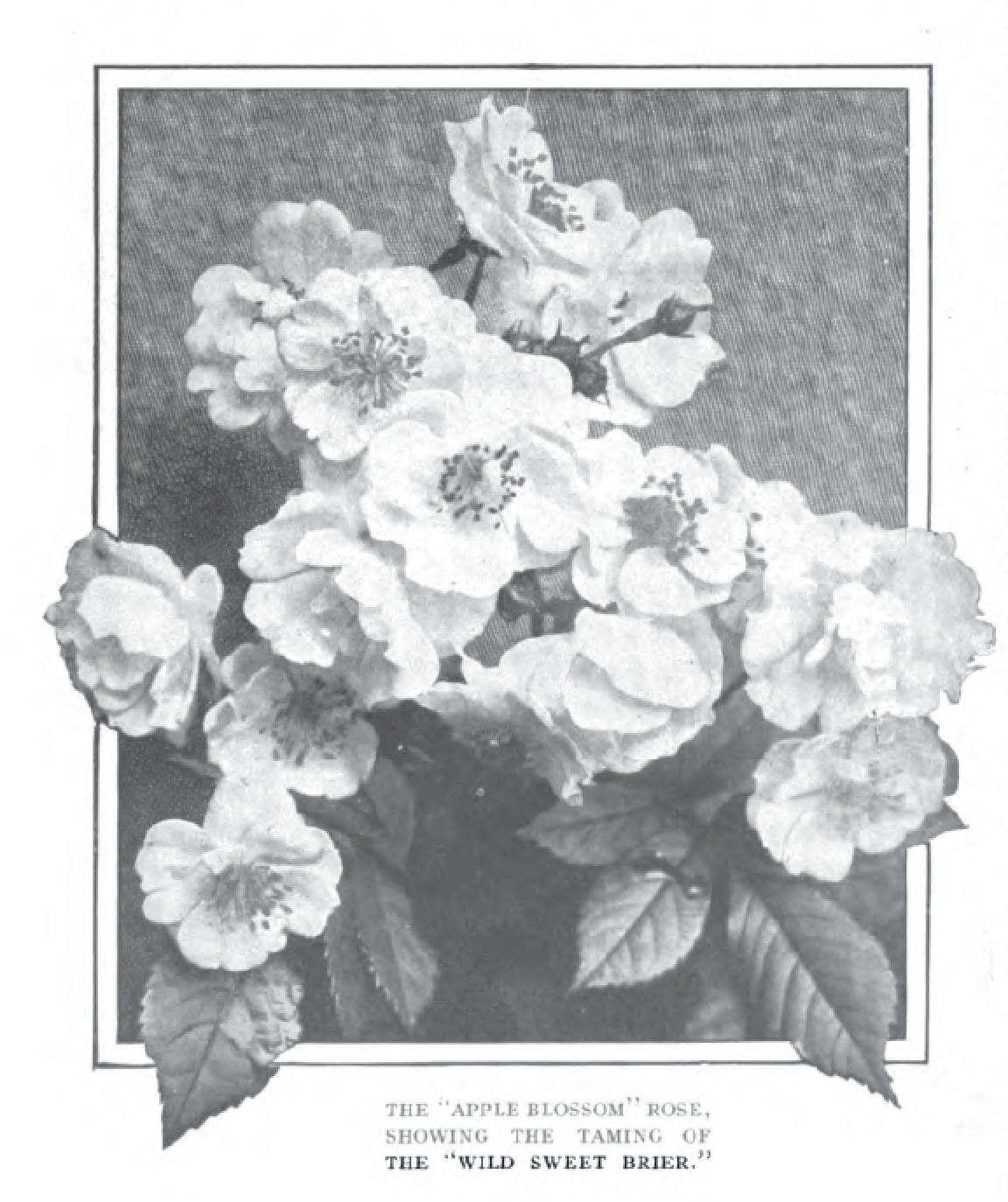

G. Jekyll put him in a book. However high he stood in legal practice, to-day he is known more widely for the work that placed him in the annals of the rose; for what he accomplished in seven or eight years was the supreme example of the right sort of novelty—that derived from wild species. He toiled over the "Sweet Brier," sweetest of all wild flowers; and his gift to floriculture was the series of useful, beautiful, scented roses known as "Penzance Briers."

They were obtained, some eighteen years ago, by mating the "Sweet Brier" with the descendants of the "Damascus," brought to England in the Crusades. To the full fragrance of the "Brier" he added the fuller bloom, the habit of flowering again and again, possessed by the "Damascus" tribe.

Hybridists who have no means of distributing their product, sometimes sell it outright to nursery men. It was thus that R. & L. Farquhar, of Boston, acquired from the Arboretum Dawson’s "Farquhar." His "Sargent" has not yet been marketed. Prices are seldom made public. The consideration may be a royalty, as for a book or a play. When a Chicago alderman a few years ago produced "Mrs. Marshall Field," he refused fifty thousand dollars for it. At Hildersheim, Germany, there is a "thousand year" rose-bush for which an Englishman offered two hundred and fifty thousand dollars in vain.

It is figured that profits from rose culture in England are ten per cent., whereas in America they are fifty per cent. Still, Americans sell plants for one fourth what the English charge. This is explained by the circumstance that American labor conditions compel growers to apply economic principles of large industries to their enterprises, and cut loose from many established rules with which many English florists are, by tradition, stupidly trammeled. What Americans do with a plow most English gardeners do with a spade; while they hew stakes by hand, we saw them by machinery. A new rose in England brings at retail one pound one shilling (about six dollars), while here the first sales are two and three dollars a plant. In Germany only two marks each were charged for the "Veilchenblau."

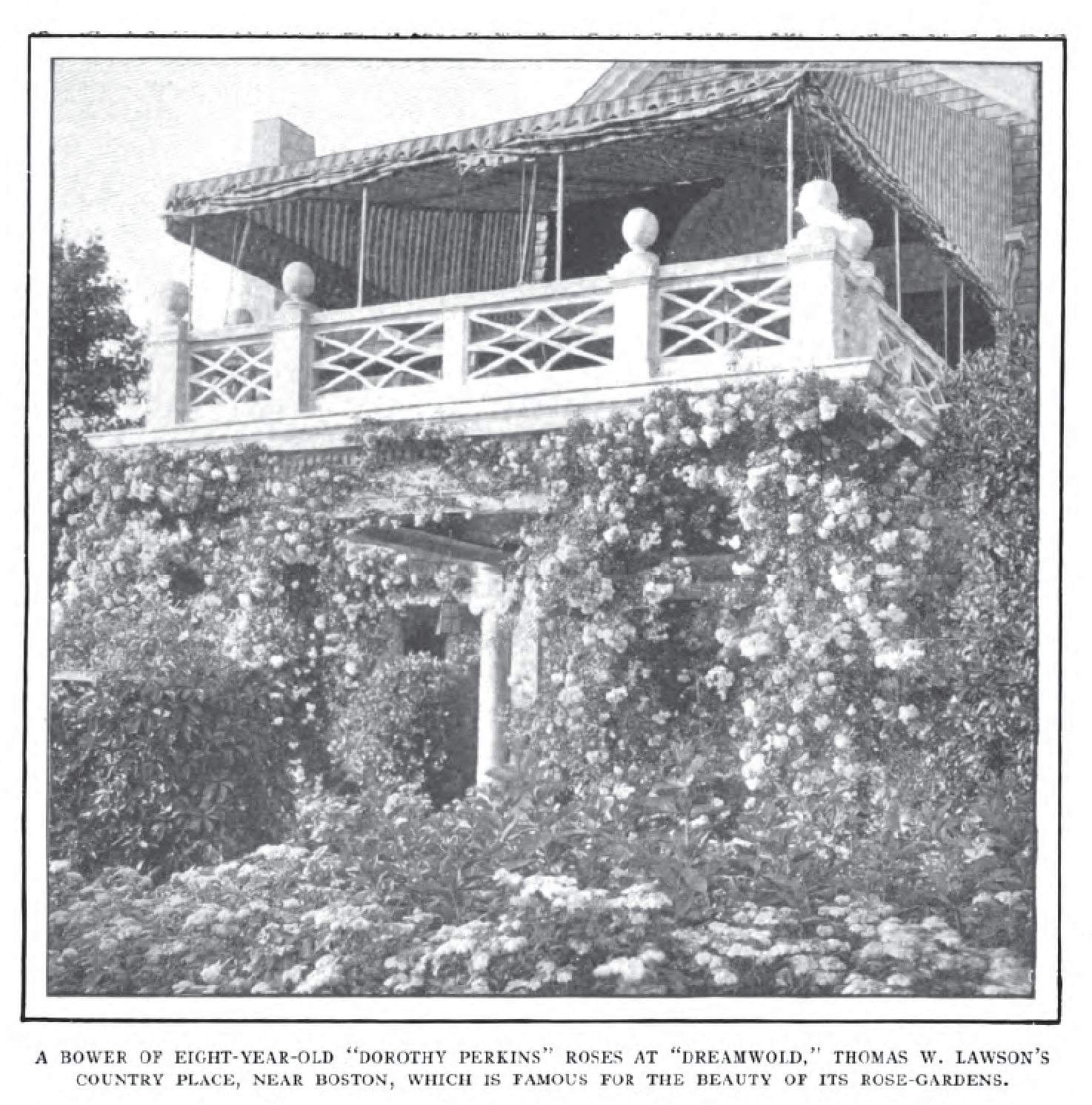

Professional growers on a large scale are captains of industry. At North Wales, Pennsylvania, there is a "works" occupying 70,000 square feet, and its annual 227,000 blossoms are calculated to yield $113,000. At Cromwell, Connecticut, A. N. Pierson’s place consists of eighteen acres, over which, perpendicularly and at angles, there are 800,00 square feet, or nearly nineteen acres, of glass. Ellwanger and Barry, at Rochester, have laboratories covering five hundred acres. They grow 300,000 hardy roses a year, yielding $175,000. Jackson and Perkins, originators of "Dorothy Perkins," have at Newark, New York, 1,000 different varieties in specimen grounds, their extensive establishment being the consequence of Mr. Perkins’s love of roses as an amateur.

M. H. Walsh’s great gardens at Wood’s Hole, Massachusetts, which English and Irish and French have honored for remarkable hybridizings and discoveries, the Waban Nurseries in Massachusetts, and those of Hoops Brothers, at Westchester, Pennsylvania, are each as big as an Iowa farm. And the Schmidt "works" at Erfurt, Germany, whence the "Veilchenblau" came, impress one as being in some distant way comparable with the great Krupp gun factories.

These, rather than the amateurs, are the modern Deucalions who are repeopling the earth with flowers to defy seasons.

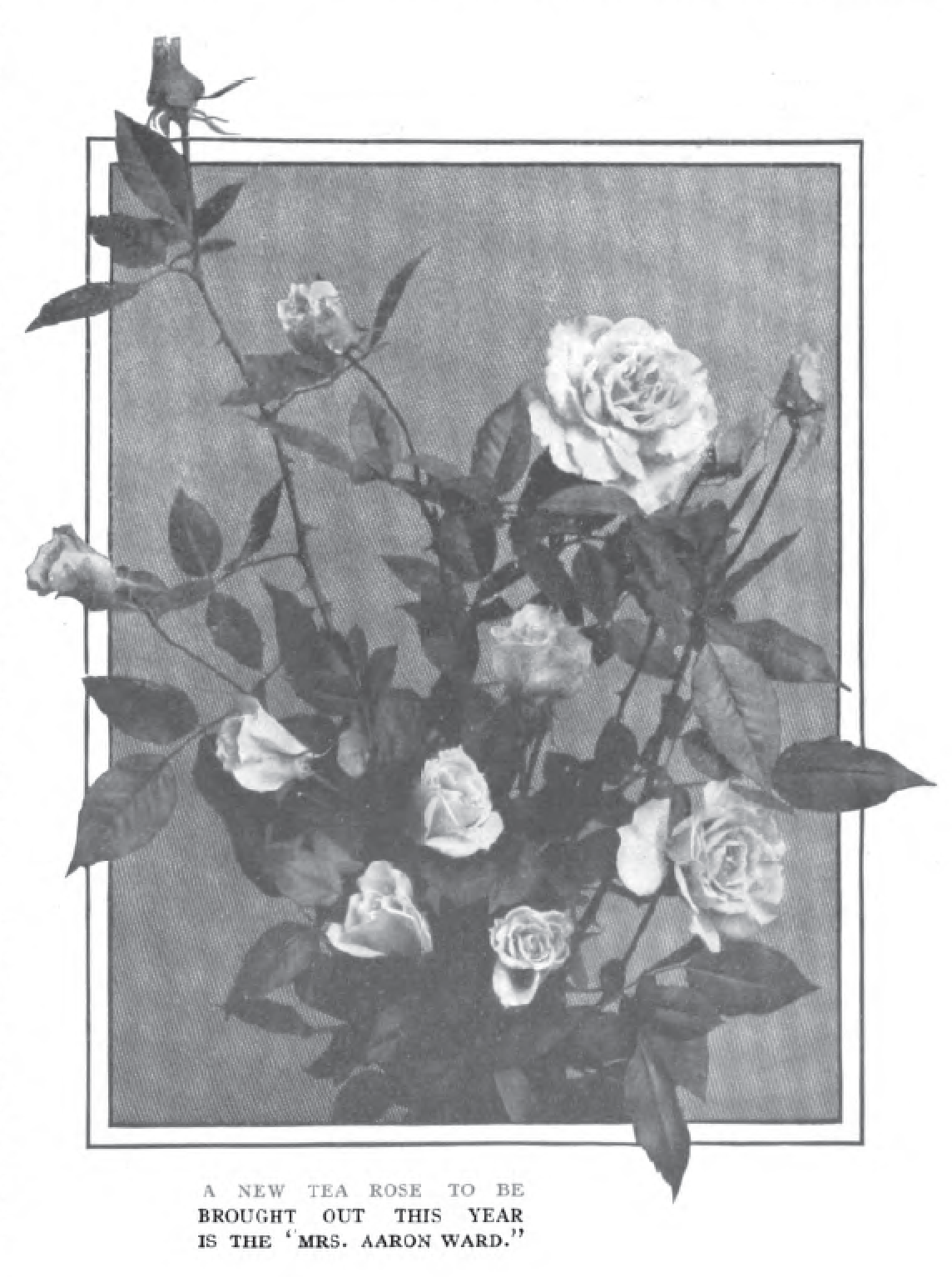

This year you will begin to hear of these new roses: E. G. Hill’s "Rose Queen," offered after four years’ trial; his "Mrs. Aaron Ward," a "tea," derived from experiments of a raiser in Lyons, France; "Sunburst, " of the same lineage, strangely distinct in every point, enormous in size, "in color like a Rocky Ford melon." Of these Mr. Hill has the American rights; plants will be sent out simultaneously in this country and in Europe, and are expected to take rank with Dickson’s Irish "Killarney" and with "Richmond." "Rhea Reid," announces Mr. Hill, "is my chief new American—a grand bedder, and successfully forced around Boston and Chicago—harsh winds have so little terror for it."

"American Climber," produced by Conard and Jones, is regarded as one of the finest recent American introductions; it is pink, with a large circle of white at the center, and remarkable for its beauty and vigor.

At Boston’s spring show, the American Rose Society’s prizes went, first, to Thomas Roland for his "Baby Rambler" and also a first to Mr. Walsh’s "Hiawatha." It indicates what still must be striven for, that the society’s gold medal for the best new rose was withheld this year.

New variations—no expert can remember half of them—have been struggling along literally under names from cabbages to kings. The ancient adage that a rose by any other name would smell as sweet, holds true. Few connoisseurs will dispute that the old Cabbage Rose is still about the sweetest and most aristocratic of all.

As I sense the flower, one ideal name was that for the American "Rose d’Amour," found now mostly in English gardens. There is something fine in "American Beauty," "Daybreak," "La France," "Coupe de Hébé," "Cleopatra." note

Red corpuscles must ever be associated with this bloom, so one may like as names "Maréchal Niel," "Général Jacqueminot," "Général Washington," note "Oriflamme de St. Louis, " "Admiral Nelson."

Modern creators of new types have haphazard methods of christening. One understands "Climbing Liberty," got by Merewether of England in the time of Lloyd George and the restriction of the Lords, or "Aviator Bleriot," of a vigorous climbing habit, originated in 1909 after the first air crossing of the English Channel. But why such names as "John Hopper," or "Dr. Hogg," or "Mrs. John Laing," or "Climbing Bessie Johnson" ?

It is no slight fame to have an admirable rose named for one. Who Mrs. John Laing was, or whether Bessie Johnson was a tomboy, is forgotten; but the roses by their names have gone throughout English, French, German, and American gardens. Last year at Bagatelle, the Municipal Gardens of Paris, "Rhea Reid" was the toast of breeders from all Europe. E. G. Hill, who bred it, tells me it was called after the beautiful brunette daughter of the railroad manipulator, Daniel G. Reid, now Mrs. Topping, who, like Mr. Hill also was "raised" in Richmond. It was for the wife of Admiral Aaron Ward that Mr. Hill named his new American "tea," "Mrs. Aaron Ward."

Admiral Ward makes it a conscientious duty to warn rose amateurs on this subject of names, saying: "Be on guard against those who announce productions of novelties under American names, which are roses well known by the names bestowed upon them by the real originator across the ocean. "Helen Gould" is really "Balduin", "Virginia R. Cox" is really "Gruss an Teplitz.""

Said my friend the rosarian:

"Investigation assures me that ‘American Beauty’ is not American at all—only another name for the French ‘Madame Ferdinand Jamain.’ Ellwanger’s book on ‘The Rose,’ published in the early eighties, did not mention this. The real identity of ‘American Beauty’ had not then been established."

All roses being either white or yellow or red—barring the two new blues (you will hear of the second presently)—imagine how breeders are put to it to indicate new tints! They have to hybridize words for their hybridized products.

Only some fifty shades of red are mentioned in dictionaries. Here are the results:

Flesh-pink; warm salmon; carnation-pink; velvety-carmine; rose-carmine; pomegranate; carmine-pink; peach-coral; silvery-rose; nasturtium-red; moss-red; rosy-lilac; shaded violet; rosy-copper; reflex-carmine; brick; madder with silvery reflexes; crimson-maroon; scarlet-vermillion; brownish; fiery; velvety-purple-red; cherry; gleaming.

As for the yellow, there are: citron; golden orange; canary; lemon-chrome; orange; saffron; ochre; orange-tinted saffron-yellow; Prussian yellow; reddish-gold; apricot; primrose; bronzy; sunset.

In white there are: silver-white; pure; velvet shaded with heliotrope; ivory; white overlaid with blush; shaded-green; alabaster; creamy; porcelain margined with mauve; flesh-white; sulphur-white; nacre; splintered ice.

"Novelty has its attractions," remarked the rosarian, "but the inherent trouble is that it does not wear well. In every relation of life you come back for wearing qualities to the true, the normal, and the natural."

"Only truth smells sweet and looks good to you forever!"

"As for the blue rose—the one we have before us?" I brought the rosarian back to the plant he had imported.

"Ah, but it isn’t blue!" he exclaimed. "Only a sort of lavender!"

"But how did Schmidt get so far?"

"That he doesn’t disclose, except to say that one parent was a seedling of the ‘Crimson Rambler,’ a variation of Wichuraiana."

New hazards and enterprises in hybridization are always done sub rosa. (You know how that phrase came into the language? The rose was the flower feigned to have been given to Cupid as a bribe to Harpocrates, the god of silence, and from this sprang the custom of hanging a rose from the chandelier at secret conclaves.) Prospecting for precious metals in wild territories, financing a war in Wall Street—these are not surrounded by muter, completer efforts to "keep it quiet" than are the tests and patient sorcery of rosarians in soils, lights, and contrary breedings, to try to bring some illusory supposition to a triumphant reality.

So my friend was not surprised that in Herr Schmidt’s explanation, the patient, scientific, delving German hybridist, while acknowledging that his product was not true blue, did not tell how he had got so far toward it.

" ‘Veilchenblau,’" wrote Herr Schmidt, "is a direct seedling of the ‘Crimson Rambler,’ not cultivated by fructification with another kind. By culture of several years, the new kind has rested constant. There have been no dosings with chemicals. The flowers appear in large umbels, are semi-double, and of medium size; when opening, partly reddish lilac, partly rose lilac, changing to amethyst, and, when fading, steel-blue; the general impression is that of the March violet. The color changes according to the place and soil. It has a substantial growth, pleasant tea scent, bright green foliage, and few but sharp thorns; up to the present it never has been attacked by mildew, and is one of the hardiest climbers. Trials of crossing with sorts apt for this purpose will be made; and probably we shall soon be able to greet the much-longed-for cornflower-blue rose."

So it was merely "the bluest" rose so far achieved, this dull, gawky plant with stout, fat stems, and, at the top, absurdly inadequate blossoms!

"No earnest striver would be content with it," said my friend the rosarian, and the propagator plainly was of the same mind.

You may imagine how profoundly Britannia was stirred by the recent actual delivery of this almost blue rose from Germany—the country which can most easily stir her up.

Immediately there came announcement of a "true blue" rose which would be put on the market the coming autumn, and make the German near-blue look as out of date as a ten-year-old battleship.

Immense throughout the rosarian world was the sensation. The breeder’s name and nationality were withheld. No absolute distrust was expressed; there was only a polite gesture indicating a resigned wish to wait till autumn and see what the new rose is like.

I have chased this second new blue through the Duchy of Luxembourg, where they know as much of roses as Holland does of tulips; through France, through America, and through England. It was located in England, but this was all that could be learned:

"It was bred by Alfred Smith, Downley, High Wycombe, Bucks, England."

How it came into being is still sub rosa.