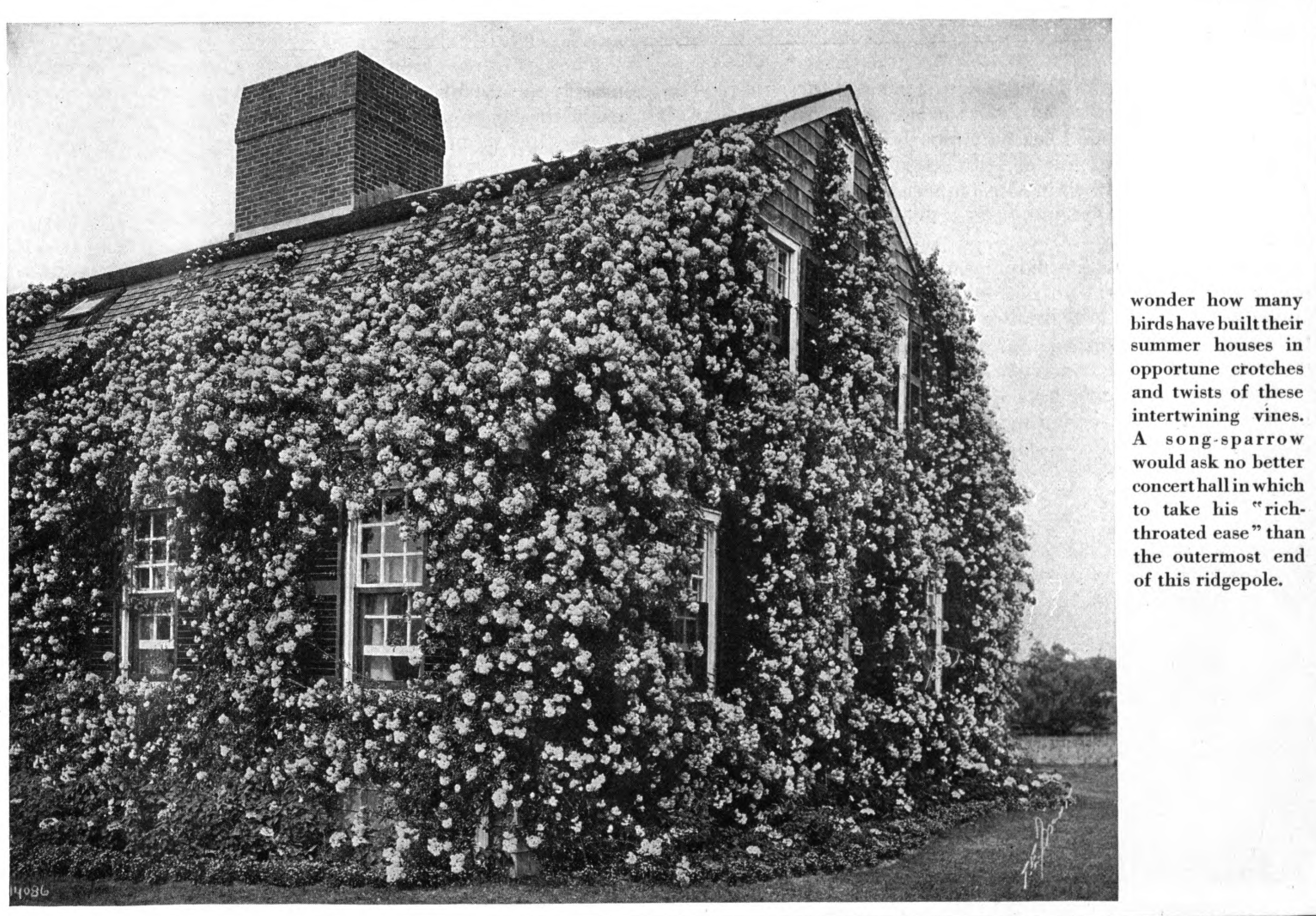

In rose time.

Rathbone, Alice. "In rose time." House Beautiful 40, no. 1

(June 1916): 36-37.

[https://library-projects.providence.edu/rosarium/view?docId=tei/rg0124.xml]

The "sweet o’ the year" is at full tide when June comes with her roses. This is a time, looked forward to so long beforehand by the possessor of even a few garden roses, that anticipation of rose-time combined with rosy memories of past Junes, might be counted among the pleasures of winter.

But there comes a moment, while roses are here, when the fleeting nature of all their beauty and fragrance intrudes upon June happiness, like the Sybarite’s crumpled rose-leaf. Impossible to keep the beauty, as that travesty of fresh loveliness, a pressed rose, proves, but storing up some of the fragrance lavished on the summer air is a pretty problem that may be worked out in two or three ways, quite easily, at home. One way is to hold the perfume in pot-pourri, such as filled the china jars of old-time drawing-rooms.

The first act in pot-pourri making is gathering fresh roses on a warm, dry day, and spreading out the petals in an airy place, away from hot sunshine, until they are reduced to half their bulk. In this partial drying lies the secret of curing rose-petals without mouldiness. Everything is lost if mould appears, as many a novice has discovered in attempting to salt down roses which held all their natural moisture.

When the petals are sufficiently dried, pack firmly together an inch-deep layer in any ordinary glazed jar of cylindrical form, and sprinkle common salt over until the petals are almost covered. Tamp it down thoroughly, and keep on adding layers of half-dried petals and salt, packing each layer carefully. Between the times when roses can be gathered for this purpose, cover the surface of the salt-curing petals with a round of stiff cardboard, and if this be weighted down with a stone, so much the better, for close impact of petals and salt is important in making this foundation for pot-pourri.

Rose, or other sweet geranium leaves, after they are torn in pieces, are treated like the rose petals in being partly dried before curing. Partial drying is, however, unnecessary for lemon verbena or bay leaves or lavender, all of which may be put in with the layers of rose-petals or geranium leaves to cure when freshly gathered. Fortunate are they who can bring in lavender from their own gardens, as it is one of the most acceptable contributions to pot-pourri. It is, however, so difficult to grow outside its chosen zones that we, who must be content to use dried lavender from the druggist’s, are apt to associate the herb with old-country gardens, and its fragrance with old-country housekeeping. Were not the "sprigs of summer" that Tennyson’s Enid laid between the folds of her faded finery presumably sprigs of lavender?

At the end of summer, the cured contents of the preparation jar, mixed with the dry ingredients listed below (proportioned to one quart of the salt-cured material), are ready for the pot-pourri jar.

One ounce cinnamon—ground

One ounce cloves—ground

One ounce allspice—ground

One ounce nutmeg—coarsely grated

One ounce ginger-root—thinly sliced

Two ounces orris root

One half ounce anise seed

Six ounces dried lavender flowers

To any recipe for pot-pourri, however, the concluding advice of the naturally good but inexact cook, to "use your judgment," applies. Each maker will, probably, through the charm of experiment, or chance of available material, vary her compound from year to year, and as any lastingly sweet or aromatic substance is acceptable in this blending of sweet odors, a pot-pourri of ideas will be found useful in the making of pot-pourri.

An old scrap-book suggests as desirable additions gum benzoin; sawdust from the fragrant cedar; grated orange peel mixed with ground cinnamon to absorb the oil of the orange (this should be salted with the foundation mixture to prevent mouldiness); the leaves of Jerusalem oak, for its sandal-wood-like odor; and a few drops of attar of roses, or any essential oil or essence. The fragrance of oil of citronella is like that of rose geranium.

The process just reviewed turns out the pot-pourri of commerce, Oriental in character. If preferred, the rose-jar may be filled simply with the cured rose-petals. This is not as lasting as the spiced mixture, but it has more of the real rose fragrance, increased, of course, if a few drops of attar of roses be added. If a fresh supply is made each summer, the year-old contents of the rose-jar, transferred to boxes with holes punched through their covers, will serve another year as perfume for bureau- or desk-drawers and chests.

Besides pot-pourri there are the rose-beads in which to store away rose-time sweetness.

These dull-black beads, with the look of carving over them, are so retentive of their fragrance, when home-made, that they are desirable, not only when strung for necklaces or as a part of tassels and other ornaments for bags and fans, but also for their sachet-like use wherever they may be kept when not worn.

The following directions for making these interesting beads, are given by one who lives among California roses, and whose success in getting excellent bead results has long been proved.

The process requires a food-grinder and its finest cutter, the nut-butter disc; an iron kettle, the rustier the better; hat pins, or pins such as are used for bill-heads; a pasteboard box cover; five drops of attar of roses, which the druggist will prepare with a little alcohol; a piece of velvet; a small quantity of vaseline scented with two or three drops of attar of roses; and two quarts of rose petals with all their little hard ends broken off.

Grind the petals over the edge of the kettle and set it away in a cool place for twenty-four hours, stirring the contents occasionally. On the following day, grind the pulp again and stir as before, repeating the process from day to day until the pulp is fine and soft and black.

The reason for using an iron kettle is to blacken the pulp of which the beads are made; if no kettle is at hand, the pulp may be blackened with equal effect by scattering four grains of crushed copperas over each pint, after its first grinding, mixing all well together, and continuing the grinding and stirring as with the kettle method.

When nearly ready for moulding into beads, the pulp should be closely watched lest it get too dry. By rolling a little of it between the fingers, now and then, the right moment for adding the attar of roses, and forming the beads, can be determined.

Just at this point, a word of warning! This work will stain the hands but being so far on the way toward our beads, we are quite likely, regardless of stained fingers, to use the palm of the left hand and the first finger of the right to form a ball of pulp twice the size of the bead wanted, and then to stick a pin through the ball, and stick the pin in the box cover until the bead is almost dry. Then, while the beads are still soft enough to take impressions, the carved effect is given, either by dotting the surface with the head of a pin, or marking it with incised lines, in pointed, diagonal, or crescent shaped groups. When fully dry, roll each bead in a little of the rose-scented vaseline, and this, when carefully rubbed in with the piece of velvet, finishes the bead making.

My neighbor brings roses into the culinary arts by simply covering their petals in a glass fruit-jar with alcohol until a flavoring extract is made. Then, if a festive occasion comes in June, she make a most æsthetic rose-cake. This is a round pound-cake, rose-flavored; iced with delicate rose-colored frosting; and, for the crowning touch, the cake is wreathed about with fresh pink roses and their own green leaves.

Less domestic are the candied rose leaves, which savor of the Orient, seeming to belong with the rose petal sweets served at "a dainty repast" described by Mr. Howells in Venetian Life.

"We lunched fairly upon little dishes of rose leaves, delicately preserved, with all their fragrance, in a ‘lucent sirup.’ It seemed that this was a common conserve in the East, but we could hardly divest ourselves of the notion of sacrilege, as we thus fed upon the very perfume of the soul of summer."