The rose of yesterday and to-day.

Matthews, Katherine Van

Courtlandt. "The rose of yesterday and to-day." Cosmopolitan (1886) 35, no. 2

(June 1903): 119-128.

[https://library-projects.providence.edu/rosarium/view?docId=tei/rg0100.xml]

"The imperishable rose" has been well said of it, and in witness to this happy truth is the fact that the mystical beauty of roses is as irresistible to-day as it was three thousand years ago, when they bloomed in the rose-gardens of Jericho.

The history and legend of the rose are woven with the very fiber of human history; and the Angel of the Flowers has so withheld the hand of Time from harming the flower to which he has given the supremest beauty, that, through periods so filled with devastation and change that dynasties have been overthrown, kingdoms vanquished and civilization become extinct, it has been ordained that the rose, undiminished in fragrance and loveliness, should miraculously escape the world-changes which swept away far mightier things, and affording delight to countless generations, should bloom on gloriously throughout the centuries.

The origin of the rose is lost upon that dim borderland where legend merges into truth, or fades away from it.

Sir John Mandeville would have us believe that a certain Jewish maiden of Bethlehem, being condemned for witchcraft on the charges of a jealous lover, and sentenced to be burned alive at the stake, declared her innocence and called upon God to show it, whereupon the burning brands turned to red, and the unkindled ones to white, roses—the first ever seen upon earth.

The ingenious pagan fable tells us that when the favorite nymph of the goddess Flora was dying, the goddess, with the aid of other deities, turned her body into a flower, endowing it with every obtainable virtue of beauty, perfume and delight; and in this heaven-born flower we have the rose.

Hindu mythology has it that one of the wives of Vishnu was discovered in the heart of a rose; and all the ancient writings abound in allusions to the rose, its fabulous origin and its brilliant influence. It was the flower which Cupid gave to Harpocrates, the god of silence, to bribe him not to betray the loves of Venus. From that time it became the emblem of silence, and through this transaction of Cupid’s, came the expression "sub rosa," signifying that anything told " under the rose" must be kept an inviolate secret. It was also dedicated to the dawn-goddess, Aurora.

It is believed that there were roses in the hanging gardens of Babylon; it is certain that they abounded in Palestine, and that the Jews possessed great knowledge of their culture and held them in high esteem. Seven hundred years after King Solomon had written of the Rose of Sharon, when the author of " Ecclesiasticus" was searching for an expression which would symbolize the highest beauty, he placed the rose among the loveliest comparisons: "As the morning star in the midst of a cloud,…as the rainbow giving light,…and as the flower of roses in the spring of the year."

The Egyptians grew roses on the banks of the Nile, and as early as in the days of Homer the Greeks had them in abundance, so that in both the Illiad and the Odyssey he could borrow figures of color and perfume from them. Sappho sang of roses, as did the Eastern poets, and those songs were taken up and continued by that long line of poets who write the poetry of the present with that of the past.

The Romans delighted in the luxury of roses, and used them in incredible quantities, covering their couches with rose-petals, and even scattering them in the halls of their palaces, and on gala occasions, in the very streets, to be trodden under foot. To them, also, belonged the distinction of being the first people to know, and make use of, the methods of forcing roses during the winter months, and so making their bloom a delight which would endure the year round. For festivals and domestic or public rejoicings they used them in profusion so unequaled as to be noticeable even in an age of reckless prodigality.

The rose found its way into Persia, where love and honor awaited it. Some of the Persian monarchs so surrounded themselves with roses that one, at least, even used them as corks for his crystal decanters; and it is from a Persian poet, Attar, that we learn of the nightingale’s hopeless love for the rose, and how, night after night, it pours its heart out in a passion of love and grief to the flower it adores.

Gradually, as we trace the history of the rose through country after country, age after age, through paths lit by its splendor of color and perfumed by the fragrance that so intensifies its charm, we find it gaining place in every part of the world, lending itself everywhere to romance and to song, with virtues of utility added in the distilling of its leaves for rose-water, in the extraction of its essential oil for attar of roses, and in the making of a quaint old-fashioned conserve from the rose-hips, highly thought of, and said to be most delicious.

Early in the thirteenth century, Chaucer said that "the savor of the rose" smote to the "heart’s root;" and, by the sixteenth century, Gerard was writing that the damask and the cinnamon roses were common in English gardens.

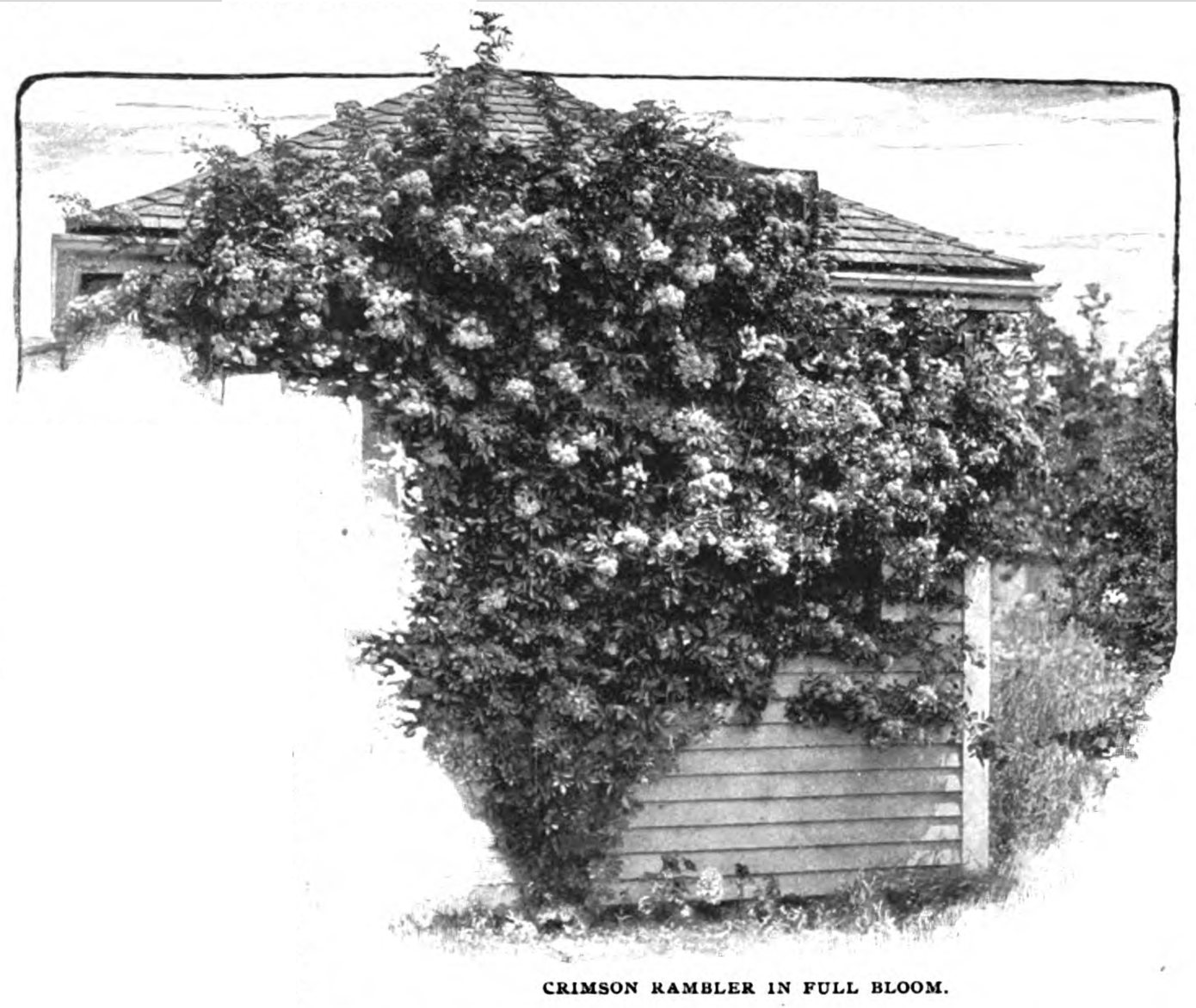

Throughout the Middle Ages runs a thread of rose-romance almost too slight to be historical, yet lending a touch of grace and lightness to matters heavily weighted with importance. It was the flower of chivalry—of love—yet sometimes its petals were stained with a deeper crimson than their own, as, in the "Wars of the Roses," when civil war rent England; of the rival factions, the followers of York wore the white rose, and those of Lancaster, the red, and there bloomed for them both "the blood-red blossom of war with a heart of fire." But peace unites, and there grows to-day, in old gardens, a rose, called the "York and Lancaster," whose petals bear both the red and white in curious stripes and markings. In one garden, not far from New York, there is a rose-bush of this variety known to be over a hundred years old, whose bloom, instead of failing with time, grows each year more lavish and profuse.

There are stories, both in England and America, some of them authentic, of yearly rentals consisting of "one red rose," and, in France, of maidenly amiability and virtue being rewarded once a year with a crown of roses. Over the mystic rites of the Rosicrucians lies the glamour of the rose, whose magic, nevertheless, appeared to help them but little to the philosopher’s stone, though it would seem that to those who love gardens, the touchstone of happiness, if not of a more substantial reward, is to be found in the cultivation of the rose.

Both, it may well be claimed, are the result of their culture; certainly, commercially, the rose has a value no other flower possesses, both horticulturally and as the source of rose-water and attar of roses. It has been suggested that in the extensive cultivation of roses, for the yielding of their essential oil, as well as the sale of the flowers, lies a field, for American women, of work both profitable and pleasant.

In many countries it is a recognized and most remunerative industry, notably in the south of France and in Bulgaria, where, in the Tundja Valley, on the southern slope of the Balkan mountains, is obtained the finest grade of rose-attar in the world. Great areas, containing thousands of acres, are devoted to rose-cultivation for this purpose. The process is to make a rose-water which must be twice distilled. It then yields, floating upon the surface of the doubly-distilled fluid, tiny oily drops, which are the attar. The high value placed upon it is more easily understood when we are told that the petals of two thousand roses are required to make a single dram of the essence.

The attar was the discovery of the Eastern sultana Nourmahal, who one day saw drops of oil floating upon a canal of rose-water, which lent its artificial delight to her garden. She noticed, with true Eastern joy in perfume, the wonderful scent which these oily globules possessed, and so it was that this delicious secret was given to the world.

The finest essence is not, as may be supposed, extracted from the most costly roses. On the contrary, the commonest varieties, the freest bloomers, such as the damask, the cabbage and the hundred-leaved rose (all of them ordinary summer roses), contain the greater number of oil-glands in their petals. It is claimed for some roses, the "Gloire de France," for example, that they possess the double advantage of containing in their petals unusual quantities of oil with the true attar-perfume, and are, as well, perpetual bloomers—a combination of qualities which makes them highly desirable for this industry.

In this country, southern California and many of the southern states afford unusual advantages of climate and of soil for roses, and the Department of Agriculture, after making extensive investigations concerning the manufacture of attar, has strongly advocated their extensive culture for the purpose of extracting attar.

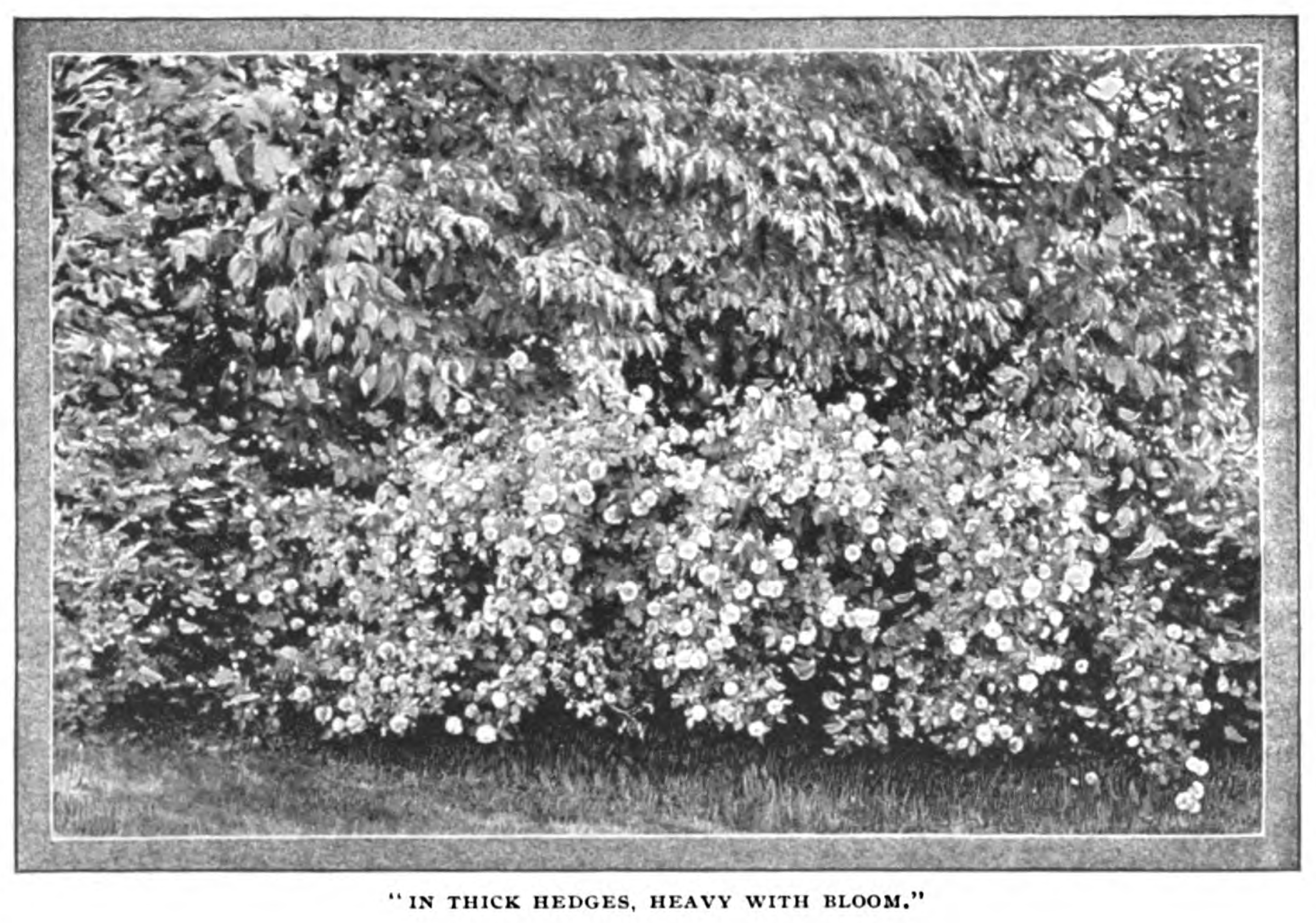

The semi-tropical climate of southern California has long made its luxuriance of roses famous. They flourish there in a wonderful profusion, even when neglected and untended, and repay the slightest care by a lavishness of bloom scarcely believable. In some localities the Cherokee and Jacqueminot roses grow in thick hedges, heavy with bloom, and in the gardens, the white "niphetos" and the beautiful "bon silence" grow abundantly, side by side with the "Gold of Ophir," the "La Marque," and a myriad of varieties as famous as these.

The rose-trees of California, obtained by budding a rose upon a dogwood stock, arrive in time at a gorgeousness absolutely unique, attaining a height of from eight to twelve feet, and with trunks nine or even eleven inches in diameter.

Of the roses of our grandmothers, those cheerful bloomers which spend their sweetness for us year after year, truly royal in their giving, affording the utmost pleasure and asking in return only the slightest possible attention from us, there cannot fail to be favorites, even where all are beloved. And, since there must even be a favorite among favorites, to any one who has spent a childhood in a rose-garden, the hundred-leaved rose will stand first and best beloved. By reason of its pretty, old-fashioned pinkness, its sweet delicacy of perfume, the generous handfuls of petals yielded by even a single rose, and, lastly, because in one old garden, at least, they grew in such riotous quantities that the guardians of the garden laid no restrictions on the picking of them, and made no such laws of "touch them not" as hedged about the rarer varieties, in spite of the fact that this rose as the distinction of coming from the Vale of Cashmere!

The damask and the cabbage roses crowded them close for favor; the "York and Lancaster" folded away the romances of history in its heart of varied white and red. Cinnamon roses were little and not especially winsome and the "seven sisters" were not very highly prized. Although of Chinese origin, they had grown to consider themselves English roses, and their owners often clung to the delusion. Among the oldest of old-fashioned varieties was the "black rose," a small, dark-purplish bloom, whose name savored of enchantment.

The "Harrison" or "yellow wreath" rose was the earliest comer, and, by reason of its innumerable prickles, the hardest of all to pick, though, the thorns once conquered, there could be no prettier rose-picture than an old, blue India-china bowl crowded full of their yellow beauty. Of white roses, "Madame Plantier" is of truly generous bloom and not to be daunted by any vagaries of season. The "Bourbon" is a later rose, and the rich perfection of its bloom more than compensates for its scarcity. The delicate "eglantine" has an individual charm hard to rival. All of these roses are summer bloomers, who, having made June an unforgettable glory, settle down to a quiet and old-fashioned rest until another June shall bring their dormant loveliness to yet another budding forth.

Of the making of books about roses, there is truly no end. From Pliny to John Parkinson, who wrote his "Paradisus Terrestris" in 1629, and dedicated it to Queen Henrietta Maria; and from Parkinson down to our own day, there are books dealing with the rose in all its phases, and yielding every degree of fascination, from the "dry-as-dust" variety to those possessed of an absorbing interest. Notable among them is "Les Roses," by P. J. Redouté, and, for a mass of information, briefly and plainly set forth, we have "Parsons on the Rose," —although, among the wealth of rose-literature, to specify but two books is to ignore a long, long list of worthies, in all of whose works may be found explicit directions to the amateur rosarian, which, if carefully adhered to, cannot fail to crown his efforts at rose-culture with success.

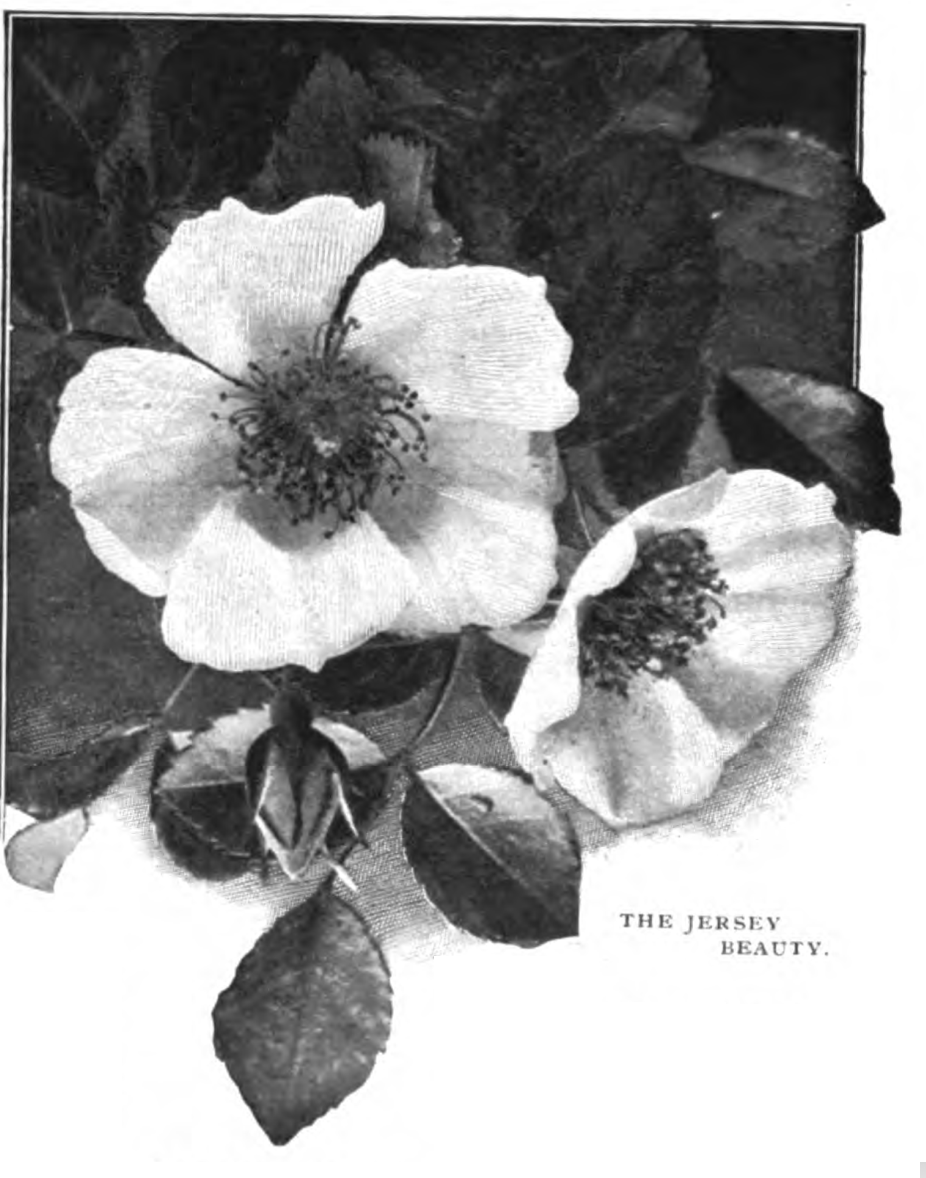

To turn from the garden-roses to those which yield their beauty only to the care and attention of the devoted horticulturist and florist, is to step into a world in which rose-beauty would seem to have attained perfection; where we may find in the single specimen the concentrated loveliness of years.

It is claimed for the twentieth-century rosarian that there us but little which Nature and his skill, working together, cannot accomplish in the evolution of the rose, in the changing of its bloom from glory to glory. Would the old Hebrews who grew them in the rose-gardens of Jericho recognize them to-day in their infinite variety? It is doubtful; for, although the rose beloved then is the rose beloved now, the forms of flower-life change so under cultivation that it is impossible to tell what form was taken by the rose three thousand years ago. It is enough to know that it was beautiful, then as now.

Capable of producing more varieties than any known flower, it has won world-triumph for itself and for the horticulturists who delight in perfecting it. In 1899 the American Rose Society was formed by enthusiastic rosarians in this country, whose object in the formation of the association was to increase rose-production in every possible way, and to stimulate public interest, in the American culture of roses, by organizing and holding annual exhibitions.

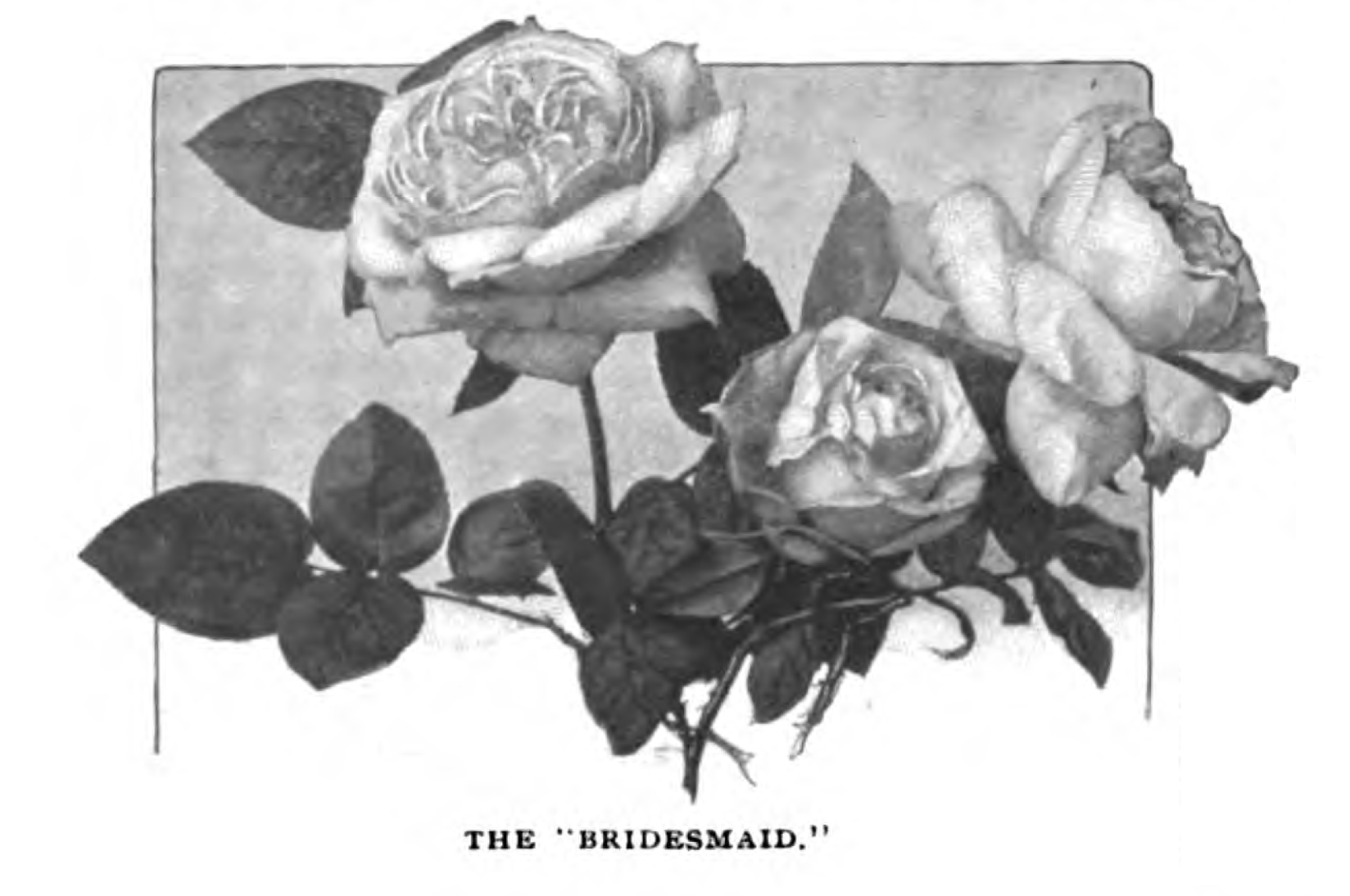

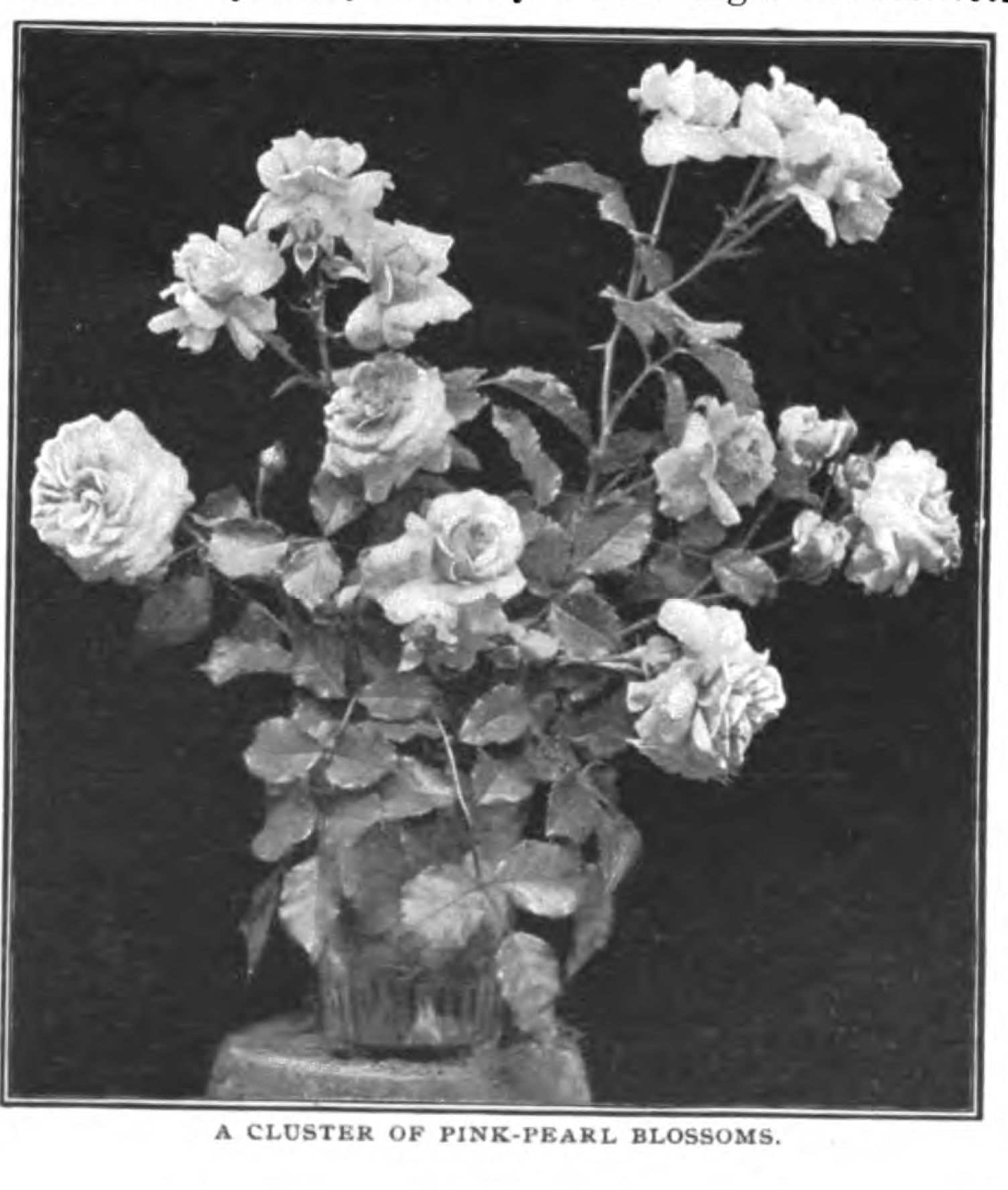

Roses had always been a most prominent and attractive feature of all flower-shows, but the annual rose-shows of the American Rose Society have met with remarkable enthusiasm and success. These exhibitions show every variety in a faultless perfection of form and color. Great interest has been manifested in them by the world of society, and, while they are being held, roses and women meet in a friendly rivalry of loveliness. New varieties have won recognition, old favorites taken to themselves new laurels; the peerless "American beauty" always leading in favor among a collection of roses whose gorgeousness of bloom is only equaled by their gorgeousness of name! Here the "bridesmaid" and the "bride" crowd the "four hundred" for admiration, and the "Queen of Edgeley" and "Alice Roosevelt" secure admiring praise.

The rose is not as common in America as it is in the Old World. It does not grow farther south than India, Abyssinia and Mexico, although cinnamon are known as far north as Point Barrow, Alaska. In most cases the rose of the poet and the rose of the botanist is identical, but popular usage has attached the name "rose" to a variety of plants whose kinship to the true flower no botanist would, for a moment admit. Love for the rose grew so strong that people emigrating from their native lands to countries where the rose was not found gave the name, as a token of endearment, to the flower newly-found that resembled it.

It is a truth which is as old as the world that nothing which is upon the earth was made without a purpose; and while following the history of the rose, we see its beauty and its use, its exhaustless loveliness and its perfumed fragrance spent lavishly through all ages for the gratification and the delight of man. We trace the rose of many yesterdays, every to-day and many to-morrows through poetry and romance, and there we find it used always as a type of the highest ideals, the symbol of imperishable love. And when, in the end, we come to ask with Tennyson:—

"And is there any moral shutWithin the bosom of a rose?"

We find it a question only to be answered as the great poet answered it, that:—

"….Any manIn bud or blade or bloom may find

According as his humors lead,

A meaning suited to his mind."