American roses and rosarians.

Lounsberry, Alice. "American roses and rosarians." Delineator 94, no. 6

(June 1919): 16-17.

[https://library-projects.providence.edu/rosarium/view?docId=tei/rg0093.xml]

The rose of the home garden and the florist window has lost its power of self-reproduction. Should it be deserted by its lovers and the commercial growers it would disappear within a few seasons. It would then be necessary to return to the distant woodlands and roadside banks to find the few wild roses that are native in this country.

But it is to be regretted that, in spite of the recognized importance of the cultivated rose in this country and the love and attention that are lavished upon, it, it has not as yet come into its true kingdom. Throughout the greater part of America the rose is most known as a decorative and commercial product—it is not known intimately to the public as an individual.

The red rose here is still regarded, except by the few, as simply a red rose; it is not known as an individual red rose, having sprung from well-known ancestors and separated from all other red roses by its peculiar personality. This is because the science of rose-cultivation is followed largely by men who grow them commercially. The amateur men and women of America who love roses lay claim only in rare cases to the fine distinction of being rosarians.

This at least is true in the Northeastern and Southern States. In parts of the West, however, there is an alertness concerning special rose knowledge that is most commendable. In Portland, Oregon, rosarians exist in considerable numbers; and the annual rose-show there is of the first rank, attracting exhibitors from all over the United States. Even the children on the streets of Portland know the names of prominent varieties of roses and discuss and criticize the points of the new ones that have appeared for the first time at the show.

Unquestionably this is an ideal condition and somewhat akin to the attitude toward this supreme flower which is held in England. For many years now English men and women have known roses, their peculiarities and their family connections, and have kept track of them with much the same degree of interest that they bestow on débutantes of the social season.

In July of 1858 the first rose-show was held in London, and since then rosarians in Britain and all over the Continent have increased steadily in number. A gentleman entering a London drawing-room is apt to comment to his hostess on the roses in a vase:

"Ah, I see that you favor Mrs. Longworth. I do not regard it as nearly as fine an individual as the celebrated Caroline Testout, from which it sported." His hostess may reply:

"I like it because it is an oddity, and because of these pink lines which traverse its petals from one end to the other."

A third rosarian may join the conversation for the purpose of saying that he has in his garden a rose with all the virtues of the two under discussion and yet which is in itself entirely distinct. And so the argument may continue, an open one to the greater number of those present.

That the American people may some day arrive at a similar degree of rose knowledge is probable. It may even be not so far distant. At present, however, those amateurs most entitled to be classed rosarians disclaim modestly the title, feeling their knowledge to be meager and incomplete.

Happily we have the American Rose Society working in this direction. Its membership at present numbers only a little less than a thousand; it bears the inspiring motto, “A Rose for Every Home.” But it can not be gainsaid that those associated with this society are nearly all professional growers, linked together in a bond from which the amateur is excluded.

Nevertheless, from such a strong center a great deal of knowledge must eventually be diffused. Mr. Robert C. Pyle is president of this society, and Dr. E. A. White, professor of horticulture at Cornell University, is secretary.

Another hopeful sign for the making of rosarians in America is the establishment at various points of test rose-gardens. These are planting-grounds where different varieties of roses are grown and tested as to their desirability for the home garden.

One such establishment of excellent merit exists at Hartford, Connecticut; and one of like standing at the New York Botanical Garden, Bronx Park. The one at Arlington, Virginia, across the Potomac from the District of Columbia, is not as yet so complete.

Still another test garden of half an acre or thereabouts is to be found at Tarrytown, New York. It is planned for the public benefit and maintained by one of the large commercial growers of roses.

Amateurs with the desire to grow roses can go to these test gardens and there select the varieties likely to do well in their home surroundings. The plants can be seen in bloom and the special conditions observed of soil, habitat and moisture under which each variety is most likely to flourish.

In fact, a knowledge is here offered to the public freely of the way in which to pursue rose-growing with intelligence. But the amateur must beware of being assailed by discouragement, for a chat of half an hour with the manager of a test garden or with any rosarian that may cross his path will inevitably impress upon his mind the fact that the price of having roses bloom as they are capable of blooming is eternal vigilance.

These queens of flowers demand an attention, a recognition of their especial needs, diet, moisture and soil such as is claimed by no other flowers. It is not that they will not live and bloom under poor conditions. Roses as a class are very hardy. They will, however, not be seen at their best.

No greater argument for scientific rose-culture could be cited than to recall the small, weak roses that every Summer are viewed and admired in hundreds of American rose-gardens, whereas if they had been given half their natural needs they would have been double the size, richer in color and showing a leafage that would have amazed by its beauty.

Usually the amateur rose-grower selects out-of-door varieties. He wishes these flowers in his garden and to pick for filling the vases in his home.

As soon as roses enter the glass-house they are nearly always under the care of expert gardeners or else they are for the benefit of professional growers. Still, there has never been a time when the amateur rose-grower had such opportunity to make his garden beautiful and for such an extended period.

Until a comparatively few years ago the amateur garden-builder planted in some selected spot a number of rose-bushes. These were of the hybrid perpetual class which during the month of June gave an outpouring of bloom that was truly a delight.

Then for the rest of the season, with the exception of a few incidental blooms, they went into a period of growth that was more or less ungainly. Year after year these hardy bushes lived and when well cared for and pruned showed no marked deterioration.

It is, nevertheless, not too venturesome to state that this class of roses has seen its best day. The hybrid perpetual will, in most American gardens, be supplanted by the hybrid tea, a happy cross between the hybrid perpetual and the monthly blooming tea-rose, the latter too delicate to be generally satisfactory for out-of-doors. The hybrid tea-rose has taken from the hybrid perpetual its vigor and hardiness; from the tea-rose it has taken the habit of constant bloom.

At present there are innumerable hybrid teas sufficiently hardy to do well in the average garden and able to provide bloom from early Summer until frost. These roses claim our foremost attention since they are the ones which more than any other attract the attention of rosarians. The future will see gardens formed exclusively of hybrid teas, abetted for arch and arbor effects by the new climbing roses, and hedged with dwarf Polianthes, small and bush-like and also able to bloom throughout the flowering season.

Each year professional growers vie with one another in breeding new hybrid tea-roses, for the pecuniary profit in putting a new rose on the market is very great, apart from the resultant distinction. At the International Flower-Show held in New York, prizes are awarded for the best rose, and these prizes run into thousands of dollars.

Sometimes the competition is so keen that the judges are obliged to sit through half the night before a decision can be arrived at and the fortunate rose set apart to receive the prize. This year no such show has been held. Government regulations owing to war conditions, the scarcity of coal during the season of preparation, and the fact that the large building where the show took place had become a debarkation hospital, all combined to make it impossible. But it is already planned that in 1920 the show will again take place and new forms of roses and model rose-gardens will compete for prizes and for fame.

The points to be considered in judging a rose are its form and color, its foliage, whether or not it is a prolific bloomer, the stiffness of its stem and its fragrance. A few years ago, when the Hadley rose won the prize of many thousands of dollars, it was largely owing to its fragrance, a point which it held against its other red-rose competitors, also fine individuals, but without sweet scent.

At the time the Hadley was regarded as an improvement on the Richmond rose, as the Richmond had been deemed a betterment of the Liberty. To-day, however, the Hoosier Beauty, a red rose bred in the State of Indiana, whence it takes its name, is thought to be a finer rose even than the Liberty, the Richmond or the Hadley.

And still above these truly splendid red roses there is one conceded to be even more satisfactory for general planting. It is the General MacArthur, a true American, introduced by a grower of Richmond, Indiana. It is brilliant crimson and very fragrant.

Its sponsor, one of the few Americans who have attained success in presenting new varieties, has here a rose of which he may justly be proud, as it is able to hold its own with any one of the Old-World varieties. Like the Liberty, the Richmond and the Hadley, it belongs to the hybrid-tea class, and forms with them a group of red roses that for the garden can hardly be surpassed.

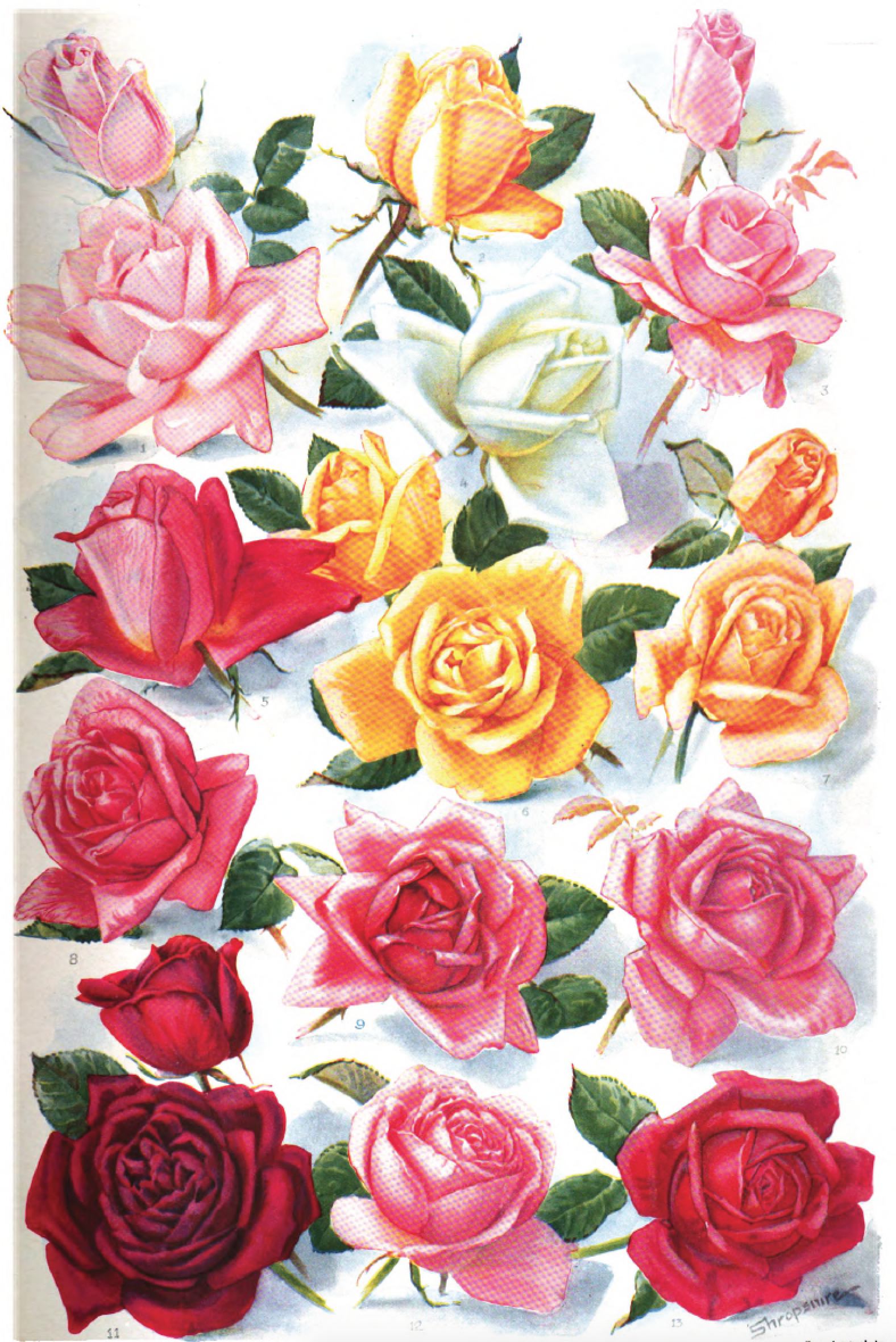

The Francis Scott Key is to-day a conspicuous rose. It is the shade of an American Beauty, but it has not so strong and stiff a stem and it is without the spicy fragrance of the better-known rose.

When the darkly toned roses for the garden are chosen, the Gruss and Teplitz must not be forgotten, for it sends out blooms of a brilliant scarlet crimson unequaled by any other rose. It is besides very fragrant. This rose, however, is not suitable to combine with other hybrid tea-roses. It is too vigorous, too strong a grower.

An original use of it is to plant it along a wall and there to let it grow to its full height and act as a cover. When it then unfolds its large, exquisite blooms it gives surprise and pleasure to those who see it used in this way for the first time.

It is conceded that the deep, enchanting brilliancy of the red rose makes it an indispensable member of the rose-garden. Even so, the amateur rose-grower can make no greater mistake than to crowd a small garden to a large one with many varieties of one color. Few varieties, and those of tested value, such as the red roses already mentioned, invariably give the most satisfactory results.

Among the pink roses there is a wide choice. The list of hybrid teas in this color is long and forms a procession of beautiful individuals that grace the world of flowers.

And among them all there is one well-beloved rose which should be known to every one. It is the Caroline Testout. This, with its deeply toned center and petals fading to rose color with satiny sheen, is a notable member of rose-gardens the world over.

The most remarkable point about this rose is known to comparably few of it thousands of lovers. It has proved itself a parent of the highest standing, and in so doing has become a very gold-mine to breeders of roses. The most prominent offspring of Caroline Testout is the Frau Karl Druschki, a hybrid-perpetual rose having for its other parent the old favorite, Merveille de Lyon.

Although Caroline Testout is pink, this celebrated one of its children is the whitest rose of all. Its appeal is like that of an exquisite bit of sculpture, for it is without tinge of either blush or yellow and the mat surface of its petals makes them appear like marble.

In the bud it recalls a pigeon’s egg. Leisurely it unfolds into a large, spotless flower. To those interested in it commercially it has returned many thousands of dollars, and it remains to-day the best all-around white rose for the garden. Unlike most hybrid perpetuals it produces flowers throughout the Summer.

Königin Carola, looked upon as an improved Caroline Testout, was obtained by breeding this most wonderful parent with Viscountess Folkstone. The petals of the Carola have a satiny sheen, and their reverse side is a silvery white.

The Lady Ashtown is also regarded by many rosarians as an improvement upon Caroline Testout.

Lady Alice Stanley is a coral-pink rose, with the inside of its petals showing pale flesh-color. It is fragrant and gives an abundance of bloom throughout the Spring, the Summer and Autumn. It is a most desirable member of the garden, showing gratitude to those who tend it faithfully.

Jonkheer J. L. Mock is another pink rose of upright, fine growth and great beauty of color and form. It is, however, not so generous with its blooms as the Lady Alice Stanley, but its long, stiff stem is a feature of excellence.

The Killarney Brilliant, a sport of the old Killarney, shows clearly its alliance with its distinguished parent. It is a deeper shade of pink than the older rose, but, like it, has not such a very great number of petals, each one being nevertheless exquisitely formed. Especially in the bud are the Killarneys recognizable. These are long and pointed and strikingly graceful. The Killarney Brilliant, when it made its first appearance at the International Show, created, as its parent had done before it, a veritable sensation.

The White Killarney is another sport from the original rose and the Double Killarney still another, displaying for its particular characteristic a greater number of petals than are possessed by the rest of its kin.

The Radiance was introduced in 1912 by a Baltimore man who is well known among the Americans whose new varieties have attracted world-wide fame. This rose has an alluring personality. In color it is salmon pink with a silver sheen which makes it appear almost flesh-color. In the bud it is long and slender and not unlike a Killarney. At present it is deemed one of the best pink roses for out-of-door culture.

The Arthur R. Goodwin is a splendid pink rose, orange-red when it first unfolds. The Pharisaer plays between the pink and white roses, being a pinkish white with salmon-color shadings, the central petals holding the strongest color. As it opens, the outer petals are seen to be strongly recurved, the characteristic of the old La France.

Mme. Jules Grolez is a bright rose, not as new as some other pink roses and yet of excellent merit.

Of course the deep-pink rose of the hour is the Columbia. It first made its appearance in 1917 and 1918, when it was introduced by E. G. Hill, of Richmond, Indiana, already famous for the number of good roses that he has given to the world. The Columbia is a deep magenta pink, compact in form and notable for its durability. Unquestionably it is a charming addition to the rose world. Had it not been introduced during the war period it would have received a much wider public recognition.

The Mrs. Charles Russell, also a new rose, is beautiful in form and of a deeper pink than the Columbia, but it does not keep as well as this prominent rose.

From pink roses to those that are light, almost flesh in color, the step is but a short one, for often a rose that is deep pink in the bud will become a delicate, pale shade when fully blown. Even so, such roses have a different quality from those that are light colored, yet not white, through their existence.

Most lovely of the light-colored roses is the Ophelia, a delicate flesh shade, paling as it opens. It was introduced by William Paul and easily won first prize at the International Show, where it gave a thrill of delight to even the most critical.

The Ophelia Supreme shows two shades in its petals, the introduction of yellow being very perceptible. The Rosalind is another new rose which is classed as an improved Ophelia.

The Prince de Bulgarie is of a deep rosy flesh color with shadings of salmon. In form it is compact and has a long, stiff stem. Its hardiness is acknowledged and altogether it is one of the best of light-colored roses from the garden.

The Antoine Revoire is an older rose than the Prince de Bulgarie and of an entirely different form, having when open many more petals. From a flesh-colored bud it expands widely into a rose, reminding one somewhat of a gardenia and holding a deep peach tone in the center. This rose has the same distinguished parent as the Caroline Testout, a lovely old rose named the Lady Mary Fitzwilliam. To procure this the Antoine Revoire was crossed with the Dr. Grill, another old-time favorite.

The Mme. Edouard Herriot is one of the most notable hybrid tea-roses on account of its unusual and fascinating color, combining coral-red, yellow and salmon-pink in a way which recalls an African sunset. When this rose was introduced it took a prize offered by the Daily Mail in London, and for this reason it is sometimes dubbed Daily Mail.

The Willowmere is in the same class of brilliant shrimp-pink and yellow coloring as the Daily Mail, and is especially lovely in the bud, when it is purely coral-red.

The Los Angeles is still another rose of extraordinary coloring and is now to be seen in most choice plantings.

Among roses that are deeply yellow there is the Mrs. Aaron Ward, its occasional shadings being of salmon-rose. The Sunburst bears well-rounded blooms of cadmium yellow. The Lady Hillingdon is one of the best of the yellow tea-roses and therefore not of very great hardiness for the out-of-door garden.

The Sylvia is the new rose which appears like a yellow Ophelia. In fact, the Ophelia. Rosalind and Sylvia are closely allied and have the added charm of being named for three of Shakespeare’s heroines. These names seem to add to their personality and enhance their beauty with suggestions of romance.

In fact, Americans are trying to get away from the practice of attaching to new roses the names of the growers who introduced them or of those who bore their financial responsibility.

M. A. Walsh of Woods Hole, Massachusetts, is well known for his success in developing new forms of climbing roses, mostly hybrid wichuraianas, a fact which is acknowledged in Europe as well as in America. Hiawatha, Sweetheart, Evangeline Excelsa and Enchantress are among the varieties that give a glorious amount of bloom during the Summer.

Dr. Van Fleet and W. A. Manda, of New Jersey, have also had success in breeding climbing roses. The one of W. A. Manda that has made an especial appeal is the Gardenia, a hybrid wichuraiana, which sends out clusters of bright yellow flowers and which in bud is also exceedingly pretty. Many have longed for a hardy climbing yellow rose and the desire is now gratified by the Gardenia.

The dwarf polyanthi seem destined to be used as low hedges for formal rose-gardens. They are constant bloomers and charming in many ways. The Cecil Brunner, Mignon, the Baby Ramblers, Kitty and Triomphe d’Orleans have been well tested; it is now simply a matter of individual preference as to which ones to take into the garden.

Every rose mentioned in this article is a thoroughly tested and established hardy outdoor denizen of the moderate and cold latitudes of America. The roses of southern California and other subtropical climates and soils are another story.