Land of roses.

Henkel, Alice. "Land of roses." Independent (1848) 74, no. 3362

(May 8, 1913): 1051-1052.

[https://library-projects.providence.edu/rosarium/view?docId=tei/rg0073.xml]

To think of the Balkan region at the present time in connection with anything but war is difficult. Yet the mountain regions of Bulgaria are renowned for an industry so full of beauty and peacefulness that the simple peasant folk engaged in it would seem to have no place in their hearts for thoughts of war.

From out of this wild mountain country comes the world’s principal supply of that expensive luxury known as attar or otto of roses, or simply, rose oil, obtained by distillation of the flowers. An ounce costs at wholesale from $12 to $16.

Bulgaria has been renowned as a rose oil district since early in the seventeenth century. A sheltered situation protects the roses from weather extremes; heavy dews, overcast skies and showers at flowering time favorably affect the oil content; plenty of timber is available for firing the stills, and many streams furnish water for cooling the condensing pipes.

The famous rose district extends along the southern slope of the Balkan Mountains. Its average length is about eighty miles, its width some thirty. The rose gardens cover about 18,000 acres, scattered thru 150 villages, with the districts of Karlovo and Kazanlik in the lead in production.

The damask rose (Rosa damascena) of the old-fashioned garden is the kind generally cultivated in Bulgaria for the oil. White roses, yielding an inferior grade, are occasionally seen. A rose garden will produce flowers for about twenty years, but only one crop is obtained in a year.

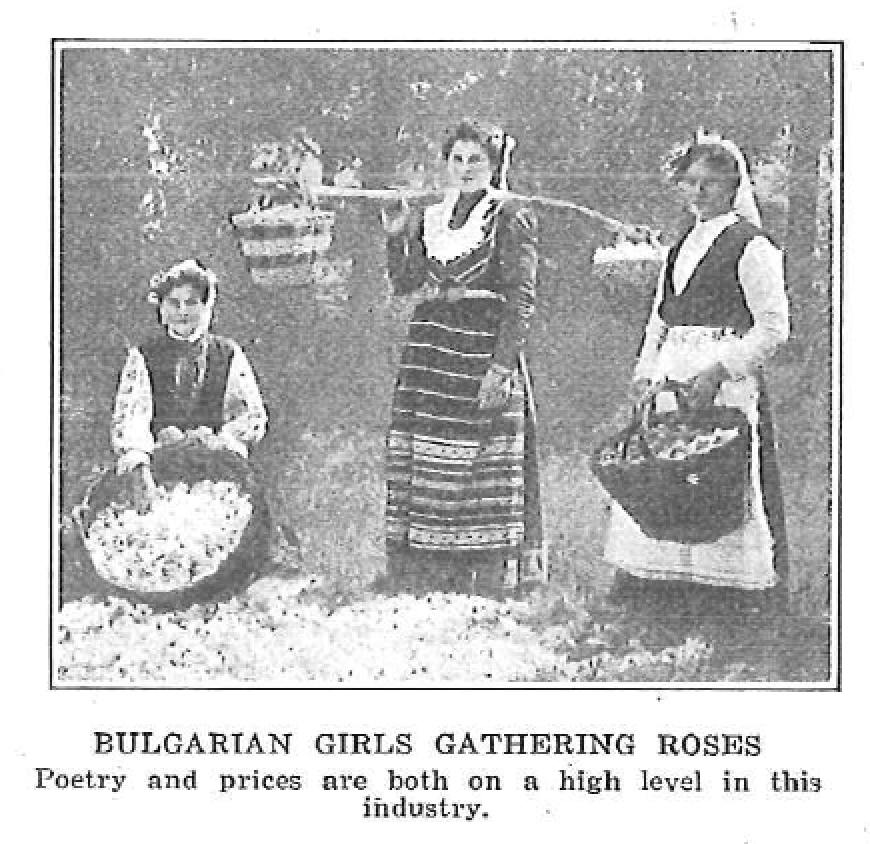

The gathering of the roses is done mostly by women and young girls. Long before the sun rises, in May or early June, these peasant girls, clad in their bright-colored native costumes, are at work. For miles around the air is heavy with the fragrance, and as far as the eye can reach are thousands of closely grown rose hedges, about the hight of a man. The gathering must be done early in the morning, while the half-opened buds are still wet with dew.

The roses are broken off just below the calyx. A sticky waxlike substance from these calyxes clings to the hands of the girls plucking the roses, and this is scraped off from time to time, to be made up later into a salve that is claimed to be good for sore eyes; it is also used for perfuming tobacco, and for coating metal necklaces.

No wonder the oil is so expensive—about 200 pounds of roses yield a single ounce of the oil. Under the most favorable conditions an acre may produce from 4000 to 4500 pounds of roses; about 300 blossoms to the pound.

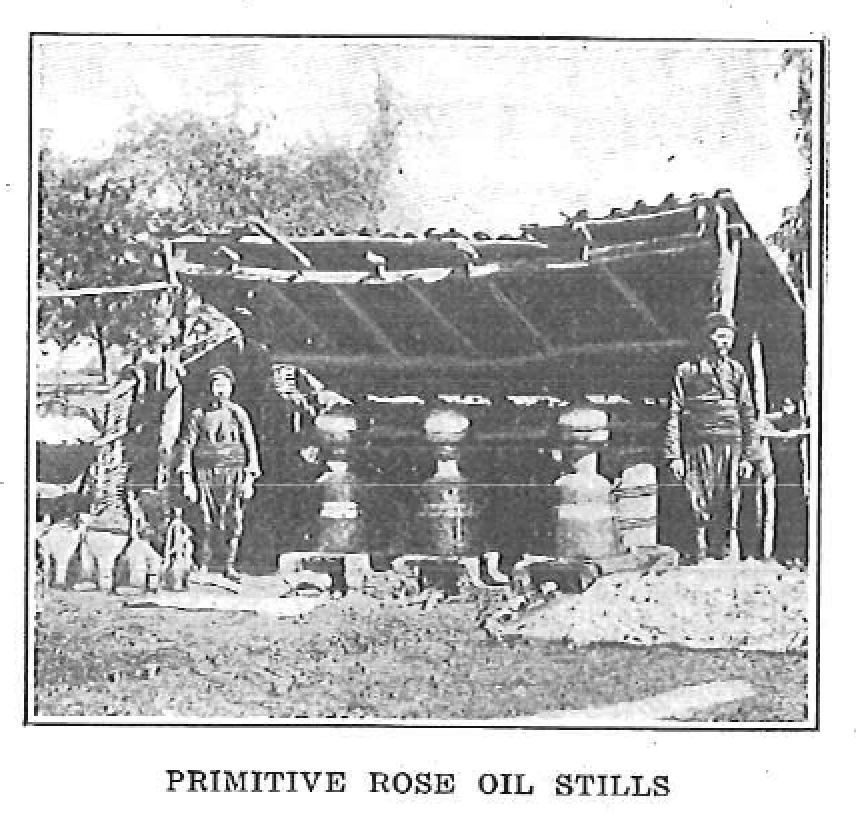

As soon as they are gathered, the roses are carried to the distillery, spread out in a cool shady place and distilled during the same day. Some of the larger establishments have modern equipment, but for the most part the process is carried on in the primitive fashion known to the peasants for ages; most frequently the distillery is merely a covered shed, open in front, under which the apparatus is placed. The rose water obtained from the first distillation is distilled a second time. Floating upon its surface are numerous tiny yellow oil globules—the attar of roses. When all the oil globules (called "butter" by the Bulgar) have come to the surface, they are skimmed off with a queer little conical spoon having a very fine opening thru which the water can run out, but not the oil.

Needless to say, attar of roses, because of its high price, is much subject to adulteration. An attractive souvenir bought at the foreign bazars is in the form of an oblong crystal flask holding about ten or fifteen drops of what may or may not be oil of rose. Sometimes the only oil of rose present consists in the dab of the precious oil on the skin covering the crystal stopper.

Alice Henkel