|

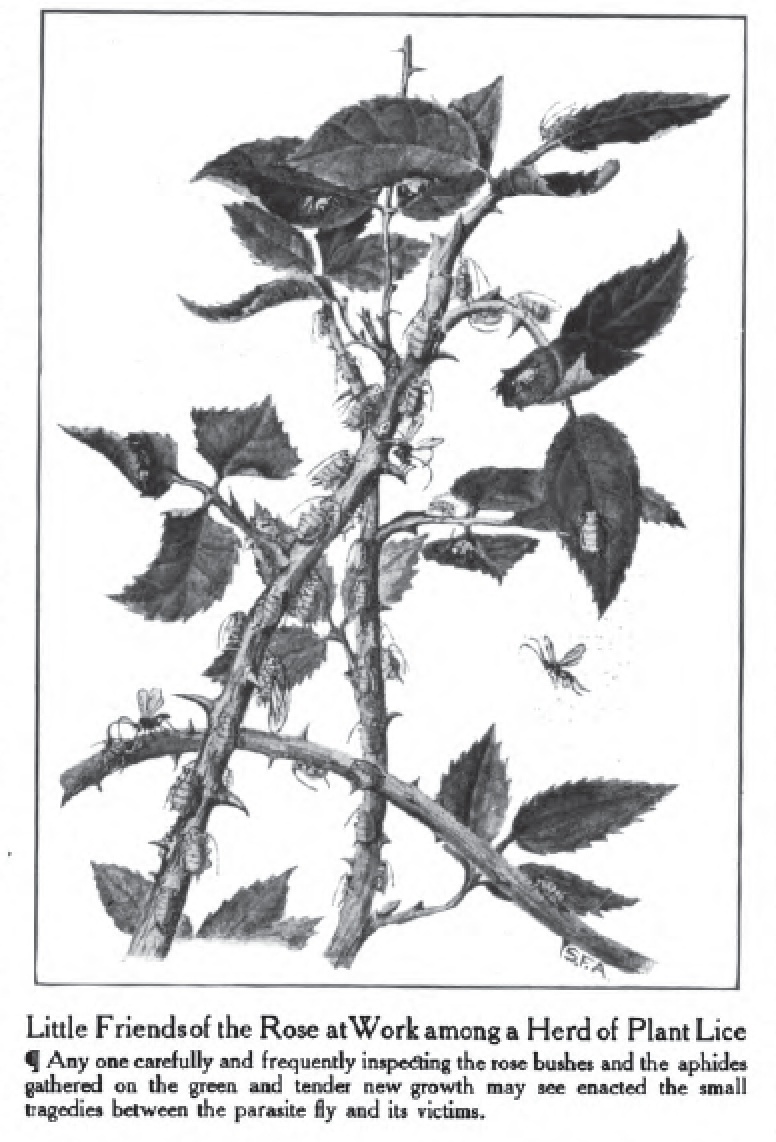

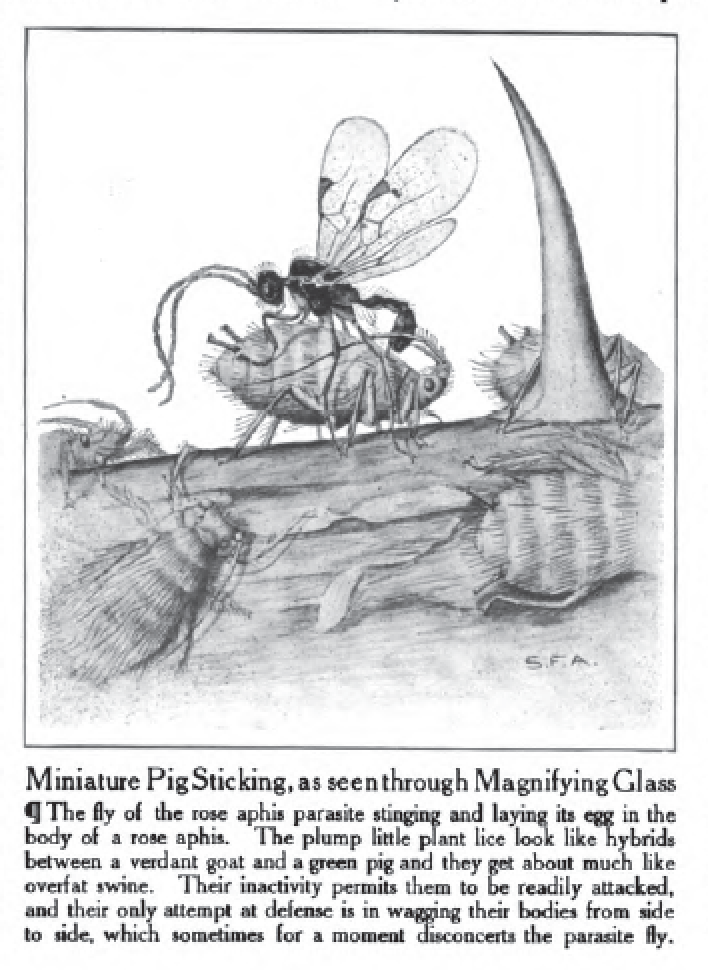

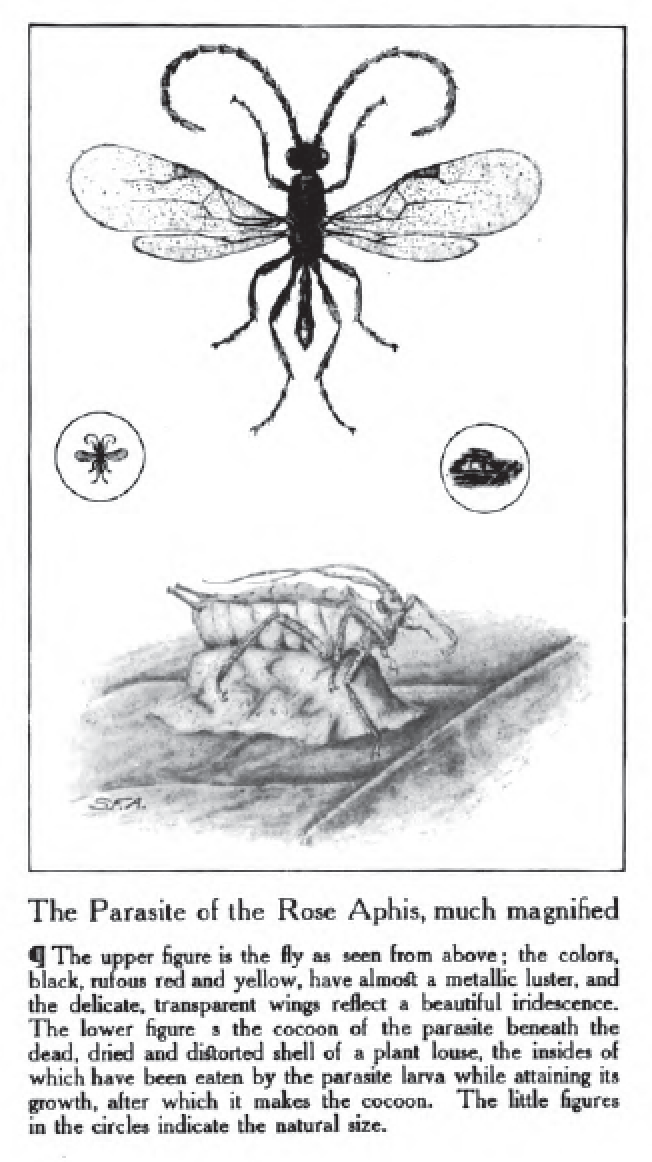

"It can never be too strongly impressed upon a mind anxious for the acquisition of knowledge that the commonest things by which we are surrounded are deserving of minute and careful attention." —Rennie. The flower-loving insects are all friends in need; but the unhoneyed flowers also have their insect friends, not agents of fertilization only, but protectors and champions that fight the battles of those that must depend on the flower stems and leaves and buds to survive. But though the flowers are voiceless, they tell us with none the less eloquence what their enemies are and how they suffer by them. Ask the rose. The withered, skeletoned leaves proclaim the enmity of the saw-fly slug; eaten leaves and others folded over tell of the larvæ of the golden-winged tortricid moth; while cankerous, eaten buds and flowers denounce the rose bug, the aphides, that crowd the green stems and leaves of the newer growth and swarm all over the tender buds. Annihilate the aphides upon a dozen stems of a thrifty bush and keep others off; then let a dozen others go full of the lice, and watch results. The number and the beauty of the blossoms will be the answer. Now, Nature generally makes a wise effort to strike a proper balance, and though we have heard this denied concerning the potato beetle, yet it is true, more or less. Thus she has furnished several antidotes for the aphis; if she did not, the little pests would become a nuisance indeed, past all calculation. This salutary purpose is effected by several larvæ of the syrphus fly, the lace-winged fly, the ladybug and a number of very small Hymenopterous parasites. Of these latter the most interesting and the most common is the pretty little fly known to scientists as Praon, which may be called the cocoon-making parasite of the aphis. Any one with sharp eyes may discover this little friend of the rose at work, and may follow, with a little care, its complete life history. At the time when the plant lice are thickest a small insect resembling a miniature wasp, or an ichneumon fly, which it really is, may be seen making its way among the fat aphides, moving leisurely and with a dignity quite beyond its size, for it usually is not longer than an eighth of a inch. It approaches one of the larger aphides and touches it with its antannæ as a means of certain identification, scent far outranking sight in such matters among insects. If this were an ant the aphis would respond with a liberal supply of the coveted honeydew, but knowing friends from foes it now slings its body from side to side, quite violently indeed for such a lethargic creature, and the little fly is pushed aside. Not liking this it moves on to another or smaller aphid with a less vigorous movement, or pausing a moment attacks the same aphis again, with perhaps better results. Choosing its position deliberately and carefully, with its slender, stiltlike legs lifting it high, it widely straddles it victim, its fore legs often resting on the aphid’s back, its slender body and long antennæ much jostled by the agitated plant louse. But now the fly is not to be dislodged. Its keen, swordlike ovipositor protrudes from its sheath and in a moment is thrust deep into the back of the plant louse, and is held for just another moment, until an egg, so tiny as to pass through the slender organ, is deposited into the very interior anatomy of the rose pest. Then withdrawing, the fly straddles off and proceeds at once to convert another aphis into an incubator, and so on, until no doubt the egg supply, perhaps fifty or more, becomes exhausted. Of course the aphis so treated does not die at once, else Nature’s plan would miscarry. It lives and goes on feeding and maintaining the same stiff and seemingly contented attitude for a little while. Meantime the egg hatches a minute, white, maggot-like larva, and this at once begins feeding on the soft muscular tissues of its host. Some little time is required for the larva to complete its growth—five or six days during very warm weather, longer when its cool. With an instinct that has ever been a marvel to the naturalist the little larva does not touch the digestive organs, the vascular system or the more important nerves for a period, thus permitting the aphis to live and feed until the appetite and growth of the parasite warrant it to eat all before it. Then the aphis dies, of course, and rapidly becomes only an outer skin, with head and legs attached. For some strange reason the aphis, not long before dying, forsakes its place among its fellows. As if ostracized for its condition, although its disease is hardly catching, it crawls away to one of the larger leaves, fastens upon it in exile and thus remains. It is obvious that this benefits the parasite; the aphis here is far less apt to be found and attacked by numerous other enemies that would endanger the life of its guest. But what can influence it? It departs from its habit, for it is altogether social and non-migratory. It removes to a less desirable pasture ground. Normally, if dislodged from the stem and falling on the leaves it crawls back as fast as its indolent legs permit to the stem again. The parasite is alone benefited, but it is out of the world, so to speak; it can not get at its host’s locomotory appendages; it is a legless, eyeless creature that at best would make a poor guide if it should get out and take the lead. But the little thing, as unintelligent as it looks, maggot-like, has perhaps a mind of its own, as we have seen. The habit is almost invariable; the victims crawl from their usual places and position themselves on the leaves. Out of seventy-one parasitized plant lice I found two on the stem and one on the tip end of a thorn, as if it thought a leaf ought to grow out there, but was too far gone to search elsewhere. Upon attaining its growth the parasite larva cuts open the aphis skin underneath and squirms part way out, so as to have full swing with its head end. Then it begins the construction of its cocoon, made, as with most insects, of its saliva, and eventually becoming, after a few hours’ work, a silken, parchment-like, bulging, tent-shaped affair, upon which the now shrunken and distorted skin of the aphis rests as on a pedestal. The parasite enters the completed cocoon and becomes an inactive pupa or chrysalis, and in a few days thereafter, if it is warm, the perfect insect, the tiny fly, emerges and takes wing to work more mischief among the rose pests. The illustrations fully elucidate the facts set forth in the text. They present a wonderful insight into a small natural force, not the less masterful because of its mimic scale. |