|

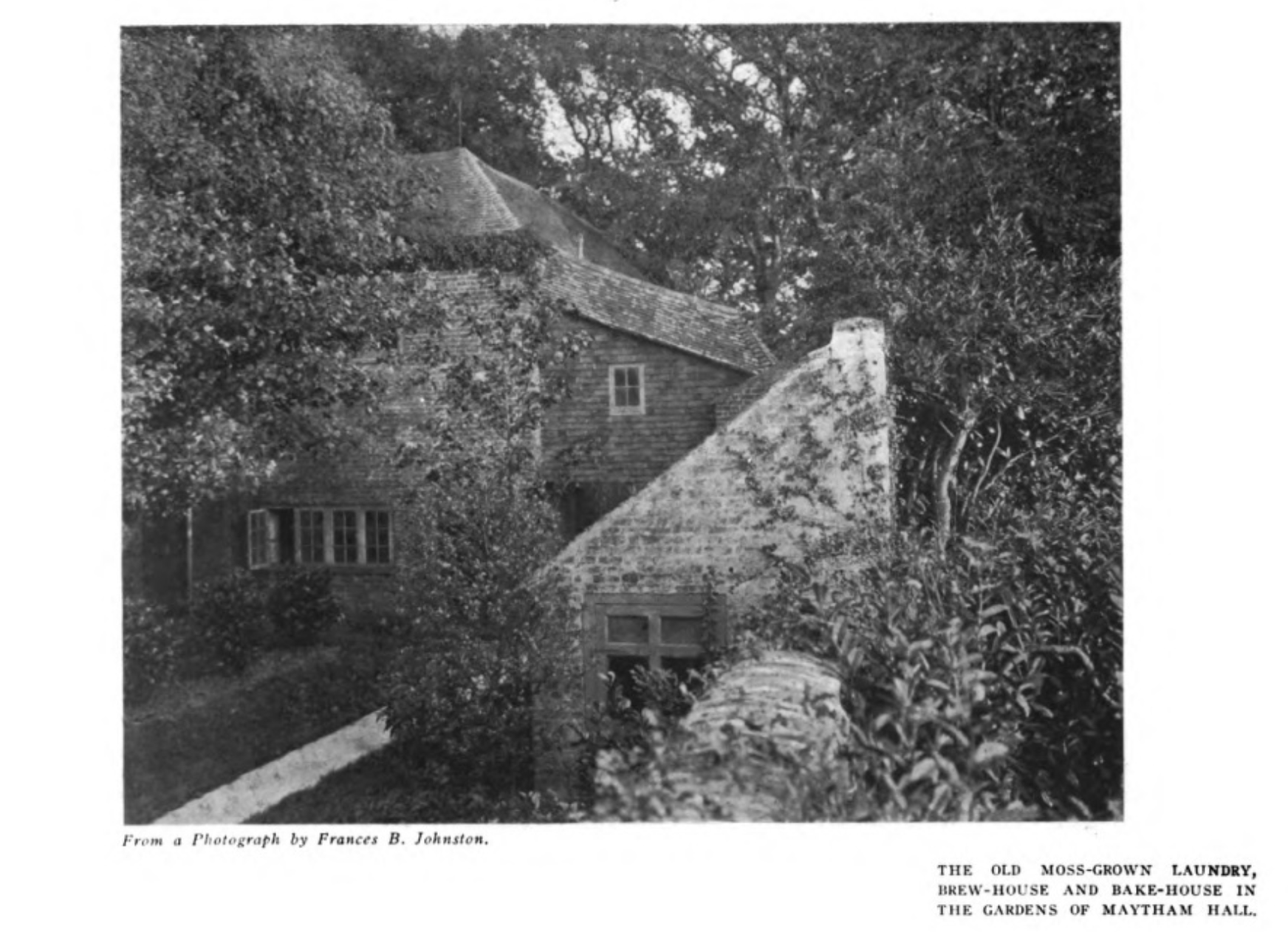

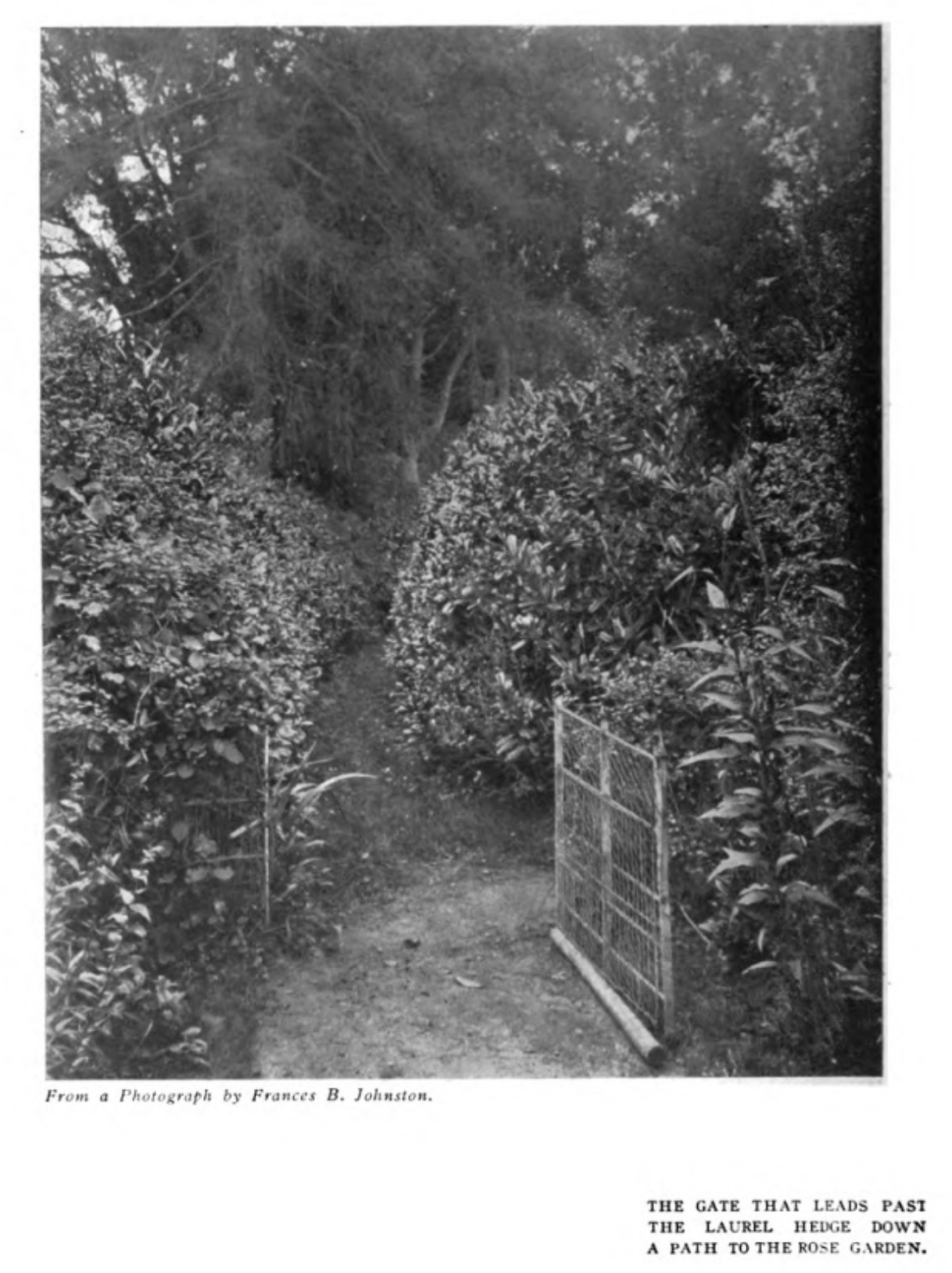

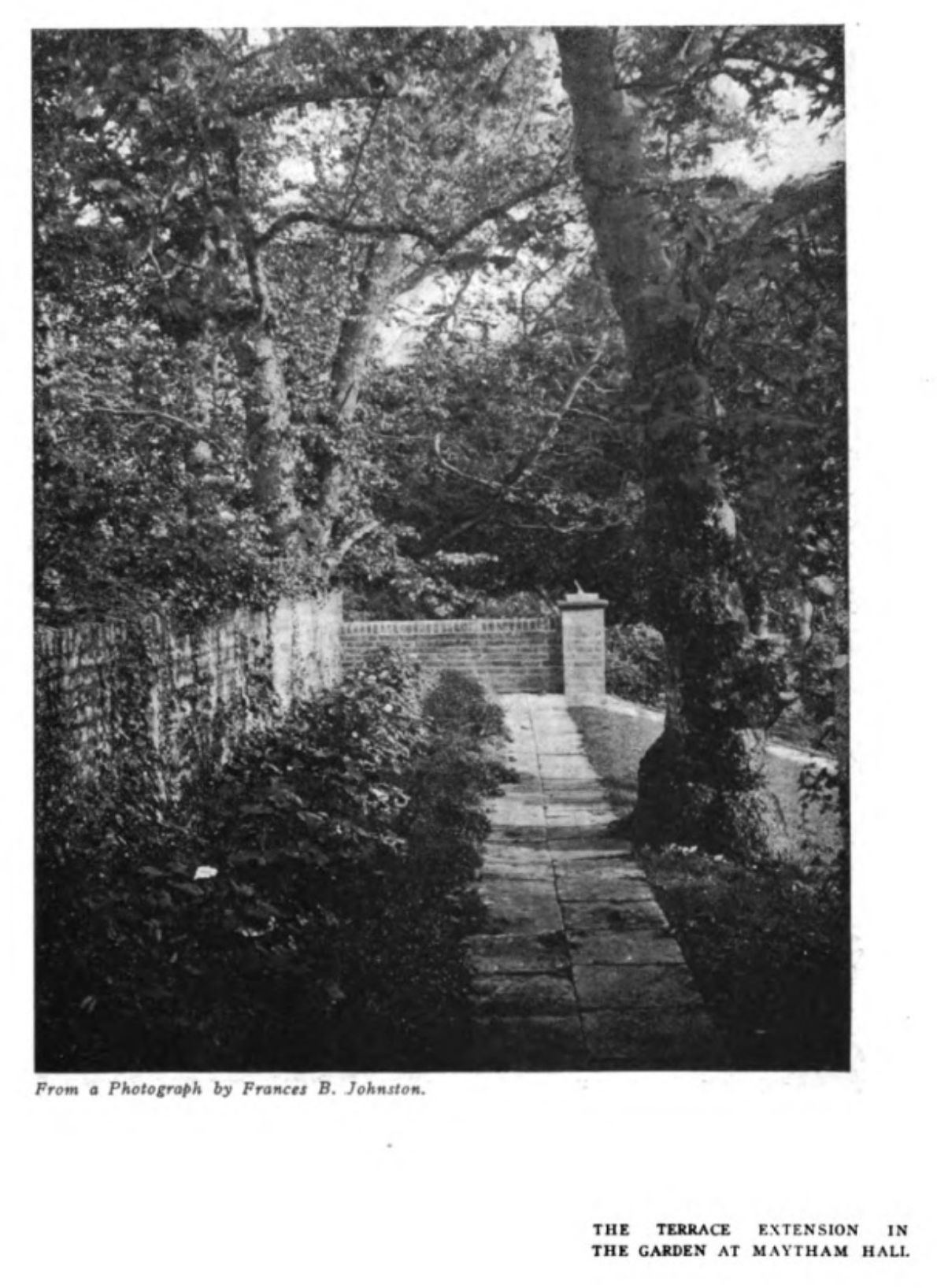

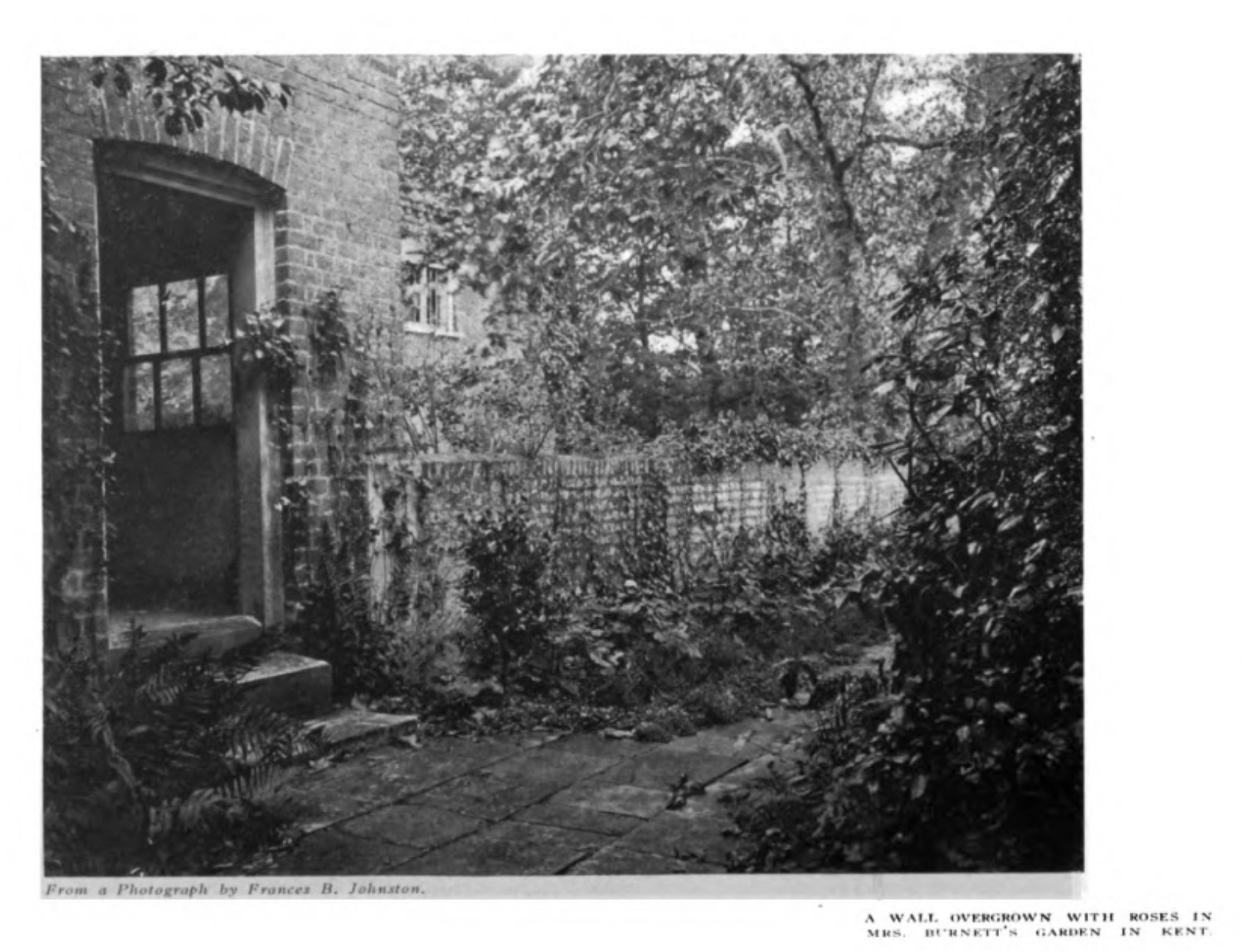

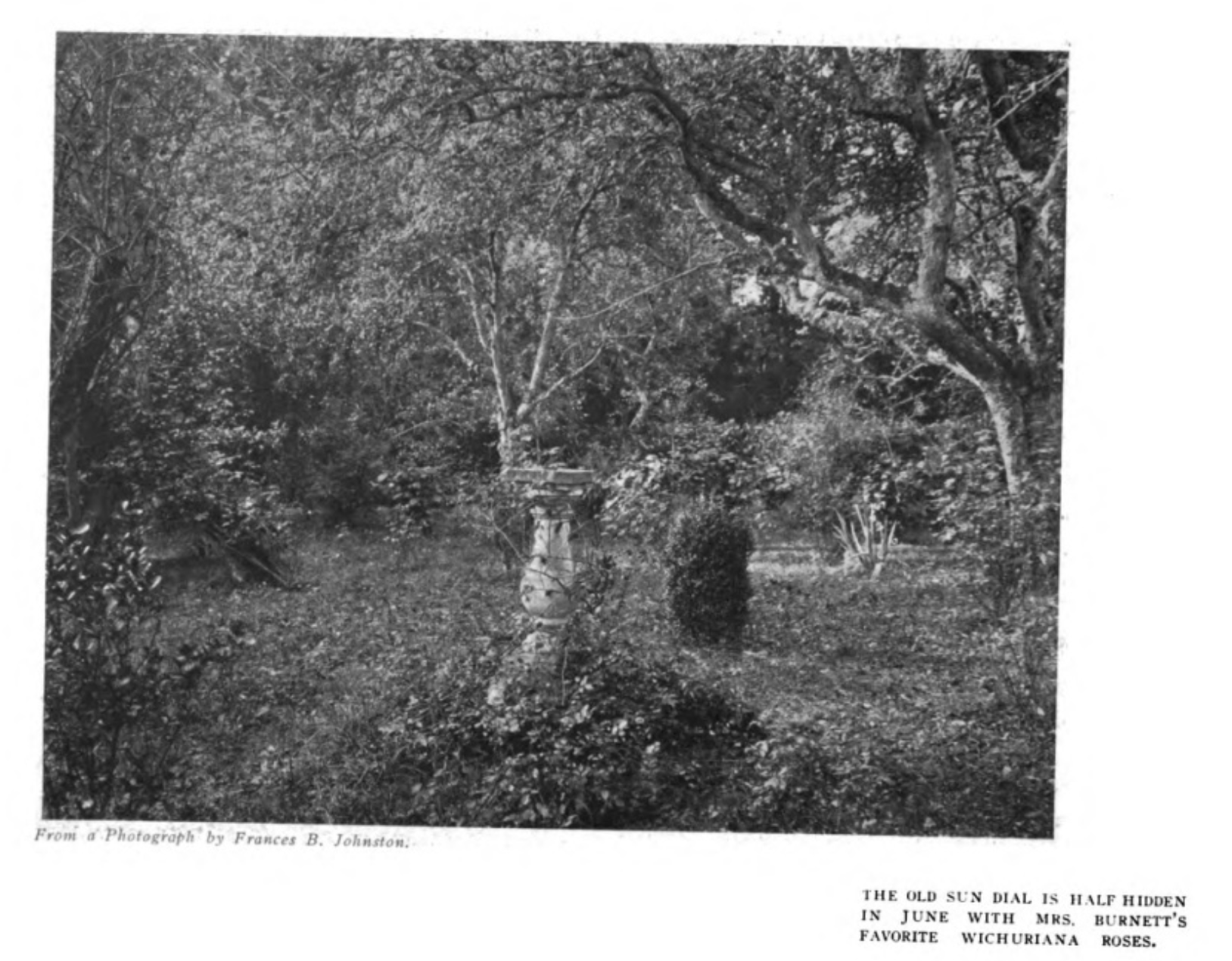

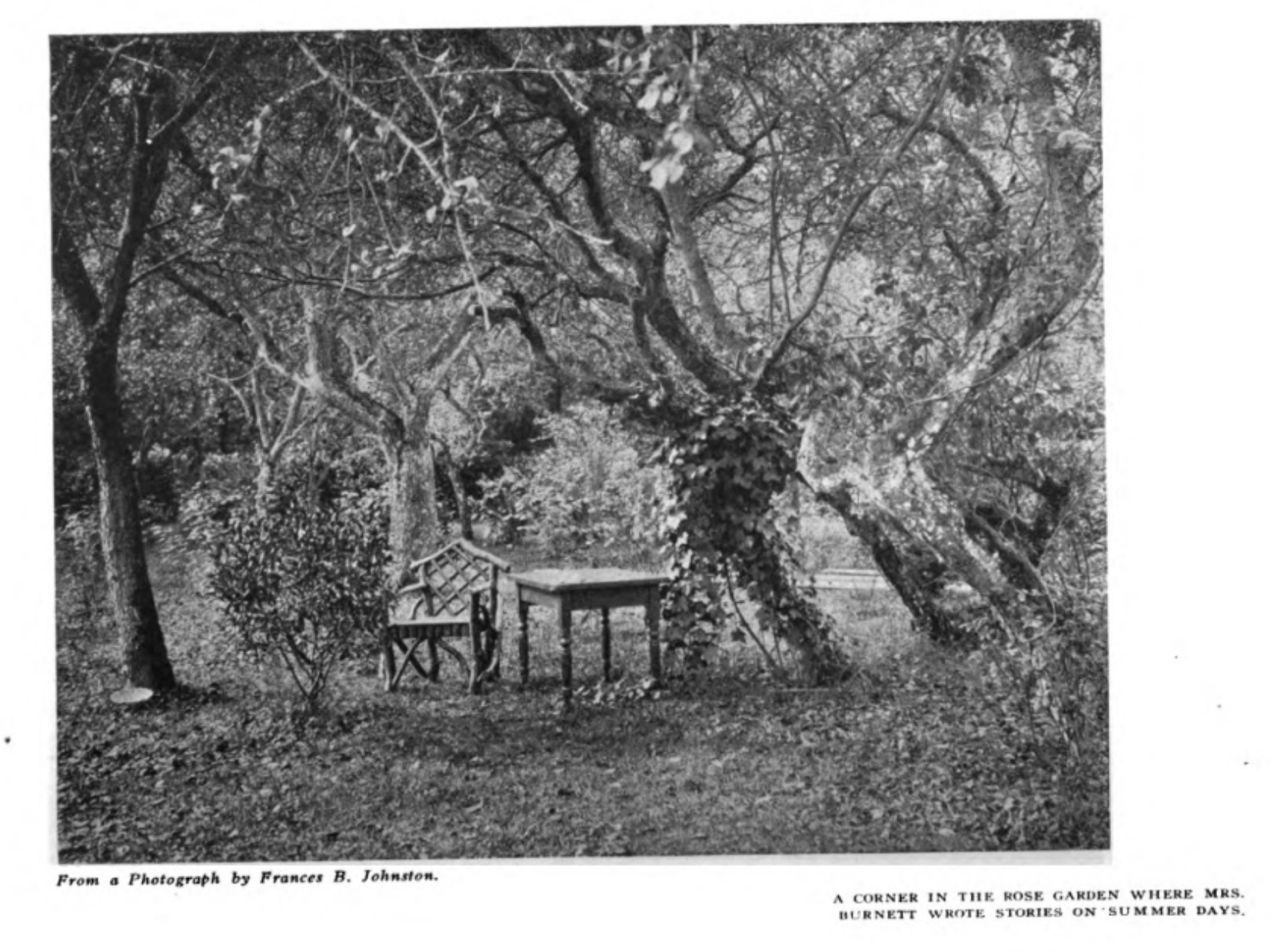

Once upon a time there was a rose garden more wonderful and fragrant than all the other rose gardens in Kent, or in fairyland, and whether you are a little girl who has lived in fairyland or an old gardener who has lived in Kent, you could not dream of a rose garden wherein there were more kinds of exquisite scents, more kinds of tints and tones of color, or more arbors and canopies and trailing vines heavy with perfume than in this old Kentish garden, which is a part of the beauty of the rolling land that Constable loved to paint, and that all artists and gardeners of all times have loved for its kind ways. Well back in the seventeenth century a rich old squire, whose name was Moneypenny, as it should be, looked about him for a fair bit of land on which to establish himself and his heirs. His eye fell upon a specially fertile stretch of Kent with a fine bit of park for hunting, with rolling hillsides for orchard lands and a lift of ground for a residence; and here Maytham Hall was established, with all the outlying houses necessary for a gentleman’s estate, with a laundry and bake house, and brew house, clustered in the shade at the edge of the park, all built of brick and red tile, with simple beauty now grown into picturesqueness under green moss and gray lichen. A wide orchard on a slope of sunny land was bounded on two sides with brick walls for fruit trees, on the other sides with hedges and the shadows of the park trees. It was this old orchard which fell under the observant eyes of Mrs. Frances Hodgson Burnett shortly after she became the chatelaine of Maythan Hall. Its days of usefulness, which were many score, were long past; its boughs were gnarled and bent with age; not in many a season had it blushed pink and grown fragrant in May. Silver-green lichen had crawled over trunks and branches, and in the fall not a patch of red or yellow came to brighten its shadowy old age. The Kentish gardener, a thrifty soul, who knew the name of every rose and every royal personage in the kingdom, was for making way with the old orchard, planting it anew with trees or vegetables. A dead orchard was just a waste of good land to his practical mind, and the relation of hoary gray trees to a flaunting rose garden was an achievement far beyond his imagination; but, though he had advice, and to spare, he had also a gracious discretion. While appreciating the philosophy of the gardener, Mrs. Burnett differed with him as the usefulness of the old orchard. Her imagination was seeing it, no longer as a relic of the thrift and domestic instincts of Squire Moneypenny, but as part of a hanging rose garden, the gray-lichened branches as supports for roses of every hue and scent, the trunk a background for crimson and white ramblers, the old brick wall top a sunlit bank for the more delicate species, the bare ground about the roots a meadow sweet where roses crept through the green and left an accent of color as they trailed from tree to tree and bloomed radiantly. The old gardener mumbled very softly as he moved out of the orchard, and the vision of the rose garden grew. It became a house with roof and walls and pillars of roses, a "house" that let in the sunlight and swayed in the soft winds, and made wild sweet lure to robin and thrush, a home where the birds sang uncaged, where time was heavy only with perfume and melody, and in the midst of all, an old, old sundial that made one but forget the hours. And then Mrs. Burnett smiled to find the discouraged gardener gone, and went away to her desk to write for rose books and figure out on paper the plans to make practical her vision of a garden, and, incidentally, to make a list of all the Kentish vicars of her acquaintance. The garden is finished, and grown into great beauty for some years past—finished, at least, in the eyes of the mere guests and stranger: to Mrs. Burnett this garden will always be in the process of making more perfect. To quote her own words, "As long as there are gardens and vicars in the British Empire, there will be fresh and useful information to be had about roses and their various virtues and shortcomings, for the vicar is to the rose family what Boswell was to Johnson. Of course there are rose books. I remember studying faithfully, "My Roses and How I Grew Them," and "Surrey Gardens," but I regarded both these valuable books as merely supplemental to the vicars. When I wanted a new climber or a rose not ashamed to bloom sweetly and busily in the shade, or when I found the demon grub advancing in vast hordes to invade my fair "Paul Nerron" or precious "Mme. Ducher" note I accepted an invitation to tea on the lawn and unburdened my troubles to a vicar, sure to be there, and never in vain. There was always wisdom and sympathy and practical first aid for the rose hospital." As Mrs. Burnett chatted, a memory of this wonderful garden came back to the writer, who had the good fortune to first see it in early June, full of color and fragrance, bird songs and poetry. From the wide porch of Maytham Hall we went down the paths with fragrant borders; we passed by the old brew and bake house, smothered in moss and trees and vines; we saw a real ha-ha, which the old Squire had built centuries ago to keep the deer from the garden, and then we came to a rosy laurel hedge and opened a low rustic gate, turning down a narrow path by the hedge, and we were in an enchanted place, a place of rose trees, of thick shade with roses dangling from gray archways. Wherever one looked were roses, however one moved the caressing fragrance of roses touched the face, and it was necessary to step most kindly lest roses red, yellow and pink should be trampled under foot. By and by when you made yourself remember that there were no fairies for poor grown-up people you looked about to find the secret of all the maze of mysterious beauty. Evidently the advice of the old gardener had fallen on unwilling ears, for through the rose vines where the leaves parted there were glimpses of the hoary trunks of old apple trees, gray with age and lichen, and overhead as the vines blew and parted in the wind there were boughs of apple trees, every twist and gnarled elbow a wider foothold for blossoms and buds and shining leaves. Not a tree ruthlessly removed, and all, from topmost twig to root, twined about, draped and hidden with roses of every rare tint and exuberant richness of hue. Where the trees grew close enough the roses spread across from bough to bough, forming arbors of trailing bloom, or where the shade from the vines was too dense, a few boughs of a tree were gone and the stump and roots a mass of foliage and luscious, fragile flowers. It was as though the trees had been planted and had grown for centuries and died and grayed away just as a framework for this magical garden. From brick wall to ancient park, not a spot unfilled with beauty. The old wall, with its rich cargo of apricots and pears trained to rest close to the sunny surface, was topped all its picturesque length with more roses that grew to an arrogant size and beauty out in the constant sunlight. And each gateway and arch hid every day usefulness under a Rambler rose, crimson or pink. One entire apple tree was a bower of "Paul Carmine-Pillar" roses, another was caressingly obscured with the sweetness of "Mama Cochet." Then, together and separately, growing in luxurious abandon, were the "Mme. Ducher," note "Prince Arthur," "Paul Nerron," the "Duke of Connaught," the lovely cream-white "Cora," note the glowing-red "Louis Philippe," note the coppery-pink "Mme. Kesal" —the despair and ecstasy of all the vicars—and the "Viscountess Folkestone;" in fact, roses from the best society of every garden in the land. Many of them, as the "Louis Philippe," notethe "Lauret Mesamy" and the "Wichuriana," begin their lovely blossoming with the first days of spring and keep up the good work until Christmas Day. The Wichuriana rose is one of Mrs. Burnett’s great favorites. It will either creep or climb at her command, so that it rests in the grass at her feet when she works in the rose garden, and trails through the trees over her head when she stops to listen to the low song of her pet robin. Besides Mrs. Burnett’s writing table and rustic chair, there are no furnishings in the garden but the centuries-old sundial, weatherworn and weather stained and hidden knee deep in June by the favorite Wichuriana, the lovely bloom in piquant contrast with the soft tones of the dial—which bit of antiquity Mrs. Burnett regards wholly in relation to the roses, never to the sun. And she is right, one does not consider time in the rose garden. It is a place in which to loaf and invite your soul. It is for poets and birds, dreamers of dreams, tellers of fairy stories, and Mrs. Burnett. The dial may have been utilitarian in the Squire’s day; but to Mrs. Burnett it is just a part of her completed dream of a rose garden. With such a hanging garden of roses as this possible, just born of an old orchard and the wisdom of vicars, why have we of all centuries and climes gone on making rose gardens as vineyards are planted, as if for revenue only; long walks of roses, through which one passed but did not tarry—with perhaps occasionally an arbor or a vine hidden porch? If roses are for more than gifts or table ornament or landscape gardening, then the world has been blind indeed, and it has remained for Mrs. Burnett to see visions in company with the poets and musicians and dreamers of all times. But in the making of a rose garden it is not all dreaming to the tune of robin calls, there is a practical side indeed to be considered, just as in housekeeping the loveliest house. There is food to the provided for the roses, plenty of it and the right sort, and winter care, and the constant battle with the evil spirit of the garden, the rose grub. "Roses are great feeders," Mrs. Burnett says. "They are greedy beyond almost any flowers. Even when the soil is most carefully prepared for them at the start and renewed regularly from season to season, the best blooms are from the best-fed plants. And in the fall they are fed for the long winter rest, roots and lower stalks covered with a rich mulch, which in springtime is spaded into the soil about the roots. Our English roses have an easy winter and are vigorous in the spring, because we seldom have the bitter stinging cold of America. So that the fall feeding is about all the winter courtesies they require of us." In spite of the fact that President Roosevelt has frightened us all so badly with regard to Nature stories, one feels somehow that an English robin would not lend itself to a misleading tale, and when Mrs. Burnett said to the guests in her garden, "if you will keep very still my robin will come and sing to you," the guests grew quiveringly silent, and waited with a distinct thrill for the final delight of fairyland. "Very still," said Mrs. Burnett, warningly, "for our ordinary stillness is a commotion to the robins." A quiver in the leaves overhead, a fine thin twittering sound from under swaying roses, an answer from Mrs. Burnett that seemed but an echo of the robin’s note, and then the fullest carol of the robin in blossom-time, a melody that always seems the color of apple-blossoms. After the song of welcome the robin flitted from bough to bough, even alighted on the table, "talking" pleasantly and hospitably; but the little final intimacies of real friendship were not for strangers to witness. When alone in the garden the robin would sing for Mrs. Burnett the soft throat song of mating time, and hop upon her shoulder or garden hat, and converse tenderly in slender robin tones. "We are just two robins together," Mrs. Burnett said, and you feel that the sting of the President’s point of view is forever wiped out by this sincerely dramatic little bird. After the robin had flown back into the vines, our hands were filled with roses and we were led away out in the park to rest under the shade of the Fairy Tree, leaves of which were given to us all to bring true the dearest wish of our hearts. |