|

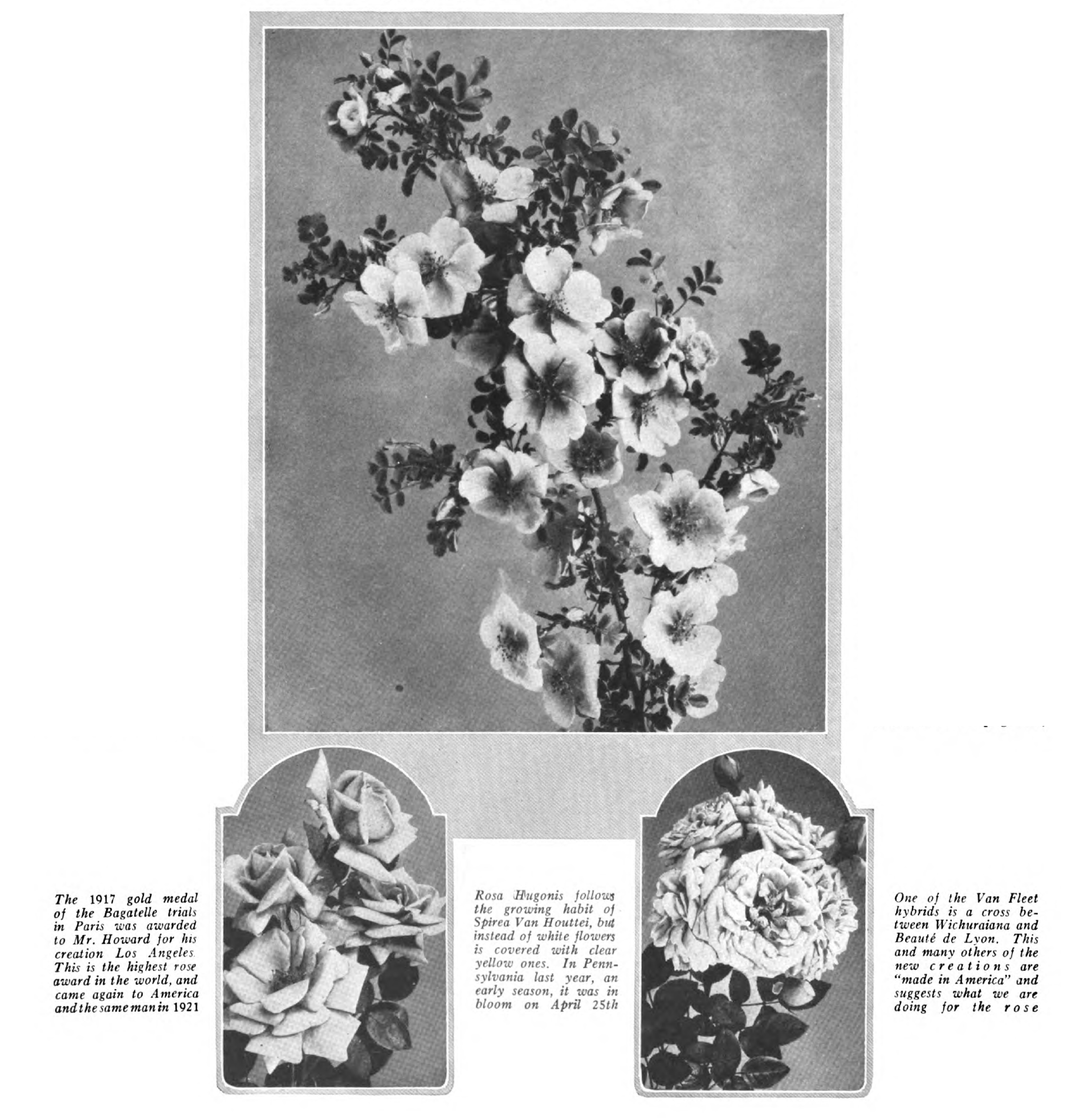

New classes are coming, and the old are better understood than ever—the future holds high promise for this justly termed queen of flowers In the past half-dozen years the rose has had more serious attention in America than in the half-dozen previous decades. As with all other flowers, the amateur, not the professional, has made most of this advance, or has made the professional advance by demanding of him better roses in variety and in quality. This same amateur has found himself, through association. In 1916 The American Rose Society had barely fifty non-professional members; in 1922 it has more than two thousand amateurs in its ranks, in forty-three states and eight hundred-odd communities, with a reach outside into sixteen foreign countries. These rose lovers are folk of thought and action, who are doing and demanding and who have in consequence set forward in the land the queen of flowers. The progress of the rose in America is recorded in the successive issues of the American Rose Annual, which I put together as editor, but which is the direct and honest expression of the rose-growers of the nation. In 1916 the florists, the cut-flower men, had much to say in this book, but in 1921 the amateurs did most of the saying, expressing themselves as to varieties and soils, protection and fertilization, literature and history, hopes and desires. It is because of this rapidly growing habit of expression that I have hopes, high hopes, for the future of the rose in America. We have a long way to go to secure the proper dominance of the rose in our country, but we are on our way. We are losing some poor ideals, and adding some that are worthy. Best of all, we are beginning to think for ourselves about roses; we are challenging the ready-made thought, mostly "made in Europe," which has delayed real progress. We are working toward roses for America and by Americans as well as in America. Who, if he will be frank about it, desires all his favorite flowers to bloom abundantly all the time? Would we want the lilac to persist through the summer, the peony to crowd the chrysanthemum, the irises to come earlier and stay until frost? Would that sort of garden permanence be really enjoyable? Is not one of the charms of the garden, the real garden, its continual, delightful and noiseless change? My garden is lovely on a May morning, and as lovely the same May evening, but it is not the same garden. I see the primroses burst into a yellow glory just where a little later, when they are through, I will welcome the longer stay of the blue and white platycodons. I love my changing, my ever new garden. It is full of attraction even in the bloomless late fall days when I may read so much promise in the ripened buds, the matured crowns. In earliest spring the swelling of these same buds, the starting of these same crowns, is a pleasure I would not miss. I do not want a tin garden, always in bloom, always alike. But what has this to do with the up-to-dateness of the rose in America? Just this: we are coming to glory in the June burst of roses, and to value them properly for their great gift to us then. We see how lovely are the single roses, the hardy climbers of multiflora-cluster and of Wichuraiana-individual-flower form. We know and cherish the "wild" or native roses, of America and of Asia, as never before. We are coming to accept and to love the rose as an item in the shrub border, to stand there with the spireas and the mock-oranges, to give us one glory of bloom as they do—but a greater glory!—and then to retire into the greenery, gathering strength for next year’s finer effort. True, we have and love the "everblooming" roses which too often prove either neverblooming, or with but an occasional tantalizing flower to keep hope alive. We struggle with these in the necessary beds which our better tastes deprecates, enduring their never graceful form and their too frequent bare and leggy stems, for the sake of the rich loveliness, the delightful fragrance of the blooms when they come. We fight the mildew and the black-spot, we worry with the suckers from the stock of the poor growth of our pets on their own roots, because we do get a Chateau de Clos Vougeot of dusky red beauty, an occasional Willowmere or Los Angeles with tints of fire, a delightful Jonkheer J. L. Mock in indescribable depths of pink. Meanwhile, and not at all neglecting these mostly foreign friends of finicky habits, we have an occasional gem of proper American hardiness and vigor to cheer us. It has taken is a dozen years to appreciate the value of Radiance, which came into commerce in 1908, and is the production of John Cook, who has bred roses in Baltimore for threescore years. We are welcoming Red Radiance, its distinct "sport." We have adopted Gruss an Teplitz and Ecarlate as our own, despite their foreign origin, because they give us roses all summer and fall without coddling. Returns were asked from all America in 1920 on the questions, "What are your favorite roses, and why?" and the answers mentioned 261 varieties. The replies tabulated by district and reported in the 1920 American Rose Annual, may be here summarized from page 118 of that volume: "In the New England States, Mrs. Aaron Ward is the most popular variety, with Duchess of Wellington a close second, and Killarney, Ophelia, Pharisaer, and Willowmere third. In the Middle States Ophelialeads, with Los Angeles second, and Duchess of Wellington, Lady Alice Stanley, Mrs. Aaron Ward, and Radiance third. Ophelia also retains its supremacy in the Southern States, with Radiance second and Laurent Carle third. Mme. Edouard Herriot and Los Angeles are equally popular in the Western States, with Mme. Melanie Soupert second and Mme. Abel Chatenay and General MacArthur third. The Central States give Mrs. Aaron Ward first place, Jonkheer J. L. Mock second, and Ophelia third." Meanwhile we have begun to appreciate the value of the roses that grow almost anywhere, do not need much protection or any coddling, and that may be used as good-looking shrubs in the hardy border, as uniquely beautiful pillars anywhere in the garden, and as climbers over the trellis or the doorway, over a fence or the rock-pile. When I began to look at roses with understanding nearly fifty years ago, the only climbing roses accessible were Baltimore Belle, with its tight-rolled little pinkish white buds and Prairie Queen, a half-wild dull crimson. Now my own garden is adorned by seventy varieties, each distinct enough to hold its place until a better sort displaces it. These roses I consider up-to-date in value and beauty, for they make the five weeks from May 24 to July 1 a feast of changing loveliness. Pure white I have in Purity and Silver Moon, both strictly American in origin, with great broad flowers in abundance, as well as in White Dorothy and Mrs. M. H. Walsh, of the cluster-flowered type, and Milky Way and "W. S. 18," both with single blooms of dainty elegance, and all American. A gamut of pink and crimson is run with Dr. W. Van Fleet, Christine Wright, Climbing American Beauty, and Baroness von Ittersum in the large-flowered class, with Lady Gay, Tausendschön, Mrs_F_W_Flight">Mrs. F. W. Flight, Excelsa, and a half-dozen more of the multiflora type, while Sargent, Paradise, Evangeline, Hiawatha and American Pillar strike the single note. The same note is hit hard by a most beautiful single rose, the Van Fleet hybrid "W. M. 5," yet unnamed, which shows a new color and habit. The yellow tones are not so well presented, but Oriflamme, Aviateur Bleriot and Ghislaine de Feligonde are really yellow and Emily Gray promises to be so. A glorious Van Fleet hybrid, not even yet given a number by that rose magician shows me enormous flowers in which flesh and pink and ecru tints I do not know how to describe. The yellows are coming, and it may be that the lovely hues of Hugonis and Xanthina, the Chinese natives with which Dr. Van Fleet is working, are to be put into climber form in his hands. No survey of the rose in America in this time can overlook these same Chinese natives. Rosa Hugonis is a new power in the shrub border, for it gives us the habit of Spirea Van Houtei with a complete cloud of clear yellow single flowers, coming long before one is thinking of rose-blooms—my plants were doing business in bloom on April 25th in 1921! R. xanthina is deeper yellow, and one form has double flowers. Both species—and they are fixed native Chinese species, not hybrids or varieties—have distinct foliage, red stems, and a lovely fall color. In the same general class of worthwhile shrubs, better looking when out of bloom than any lilac or mock-orange or weigela, are the hybrids of Rosa spinosissima, the Scotch or Burnet rose. The variation called altaica, now by some erected into a species, gives us a rounded shrub of three or four feet, covered early with a mass of great white single flowers. Dr. Van Fleet has some breath-taking hybrids of altaica and Hugonis, and one of Hugonis and Radiance, that will certainly make the nurserymen and the landscape architects stir themselves when they become available. They are, thank heaven, purely "made in America," and the aggravating restrictions of Quarantine 37 cannot shut them out. Indeed, these "new creations," of far more real value to the East than any productions of Burbankian bombast, are to be sent out under a thoroughly up-to-date arrangement between the Department of Agriculture, in which Dr. Van Fleet works, and the American Rose Society. It is not generaly realized that it is impossible for a Federal department to sell anything in an ordinary commercial way, or indeed to propagate any new plant in trade quantities. The arrangement between the American Rose Society and the Department continues the conventional distribution arrangement so far as it may be called upon by Congressmen, but also puts material for propagation into the hands of the American Rose Society which offers it impartially to all its trade rose-growing members under an arrangement prescribed by the Department. This arrangement fixes a maximum retail price, provides uniform and accurate descriptions, and earmarks any profit to the Rose Society, so that it may be used in the general interest for rose research. The first rose, available I think in 1923 under this up-to-date contract, has been named Mary Wallace, in honor of the daughter of the Secretary of Agriculture. It is a truly lovely rose, of a deep and lively pink in an informal and attractive shape, and it made at Dr. Van Fleet’s Bell experiment station a wonderful low hedge, good enough without flowers, but superb in its early June flood of blossoms. Mary Wallace will also climb with vigor in rich ground, acknowledging poor soil only by assuming the shrub or hedge form. It is not hard for any reader to realize that I believe in these once-blooming shrub and climbing roses for their rightful and extensive use, and that from a world-look I am assured we are to see the far more extended use of good roses as shrubs and lawn objects. But American hybridizers are not behind with the recurrent-blooming hybrid tea roses. In purely garden sorts we are well ahead, for the 1921 award of the Bagatelle trials in Paris was to Miss Lolita Armour, a rose of wonderful coloring originated by Howard & Smith, of Los Angeles. This gold medal, the world’s highest award for a rose, is the second in five years coming to America, and to the same grower. Mr. Howard took similar honors in 1917 for his Los Angeles rose. Probably twice as many roses are grown under glass in America for my lady’s corsage as in all the rest of the world combined. A rough estimate two years ago put the quantity at not less than a hundred million blooms. The urge for new varieties is consequently strong, and great rosarians are continually at their patient work. The high standard set, and the basis of commercial honor assumed, appeared in the late fall of 1917 when one grower, who had announced a wonderful new pink rose, and had sold to florists who took his word more than a hundred thousand plants for early delivery, withdrew the variety and canceled the sales because the variety had developed a curious variation in color and habit. It is known that other new roses in this class are coming. They are not of immediate interest to the garden-grower of roses. though some of these florists’ roses develop, or escape, successfully into the garden. For example, Columbia is now a very beautiful and vigorous garden rose, as it has gotten outdoors from its greenhouse triumph. Premier is another of these good escapes, and the favorite Ophelia came to America to live indoors, now finding our gardens quite congenial. The year 1922 will witness the general trial of several new foreign roses, doing well in Europe, but purely a gamble in America. Someone will probably worry through the Quarantine 37 regulations a German rose, Reinhard Bädecker, which is claimed to be a "yellow Frau Karl Druschki," a claim that is exceedingly important if true! A prominent American grower is prepared to send out the chef-d’oeuvre of the greatest French rosarian, Monsieur Jules Pernet-Ducher, who has named this clear yellow hybrid tea for the loved son he gave to France, Souvenir de Claudius Pernet. England and Ireland have many new roses, but not one in twenty-five ever catches on in America. This is because they are bred in and for a climate very different from ours. The humid air of Britain does not prepare roses for the American Sahara of the Middle States in summer, nor the alternate zero winds and brilliant sunshine of our winters. It is for this reason that the American Rose Society is earnestly fostering the trial gardens for the testing under our conditions of these new candidates for favor, and is as earnestly favoring the promoting of the production of roses in America by Americans for America. There is no narrow sectionalism in this latter position; it is a position of necessity, of justice to the rose. The rose in America is decidedly up-to-date in 1922, and it is rapidly gaining in quality, position and prevalence. |