|

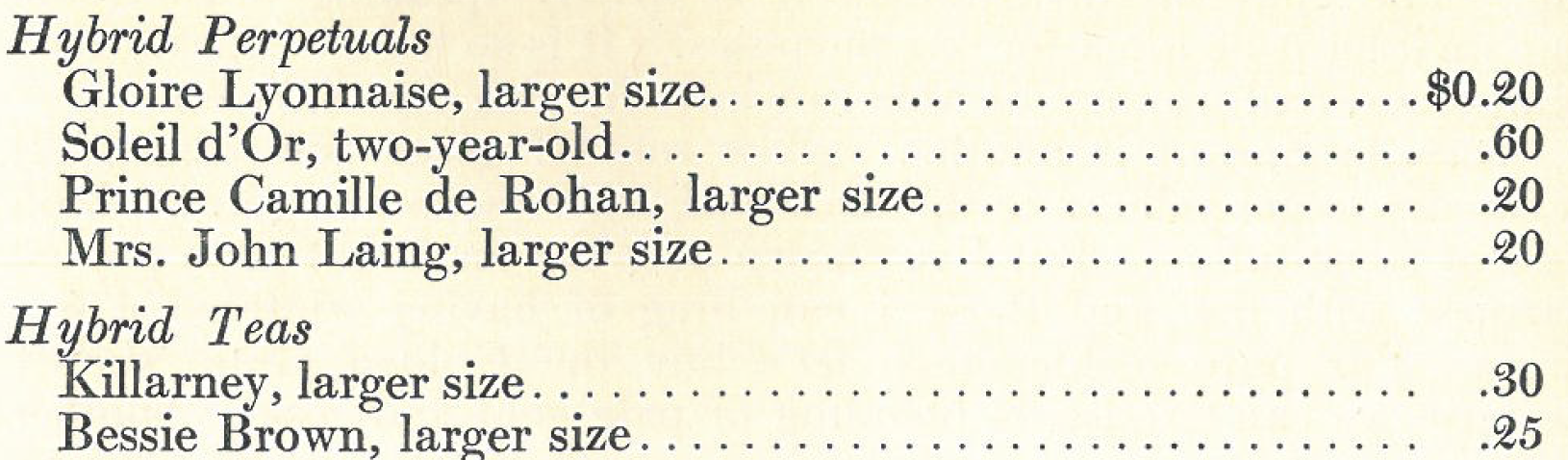

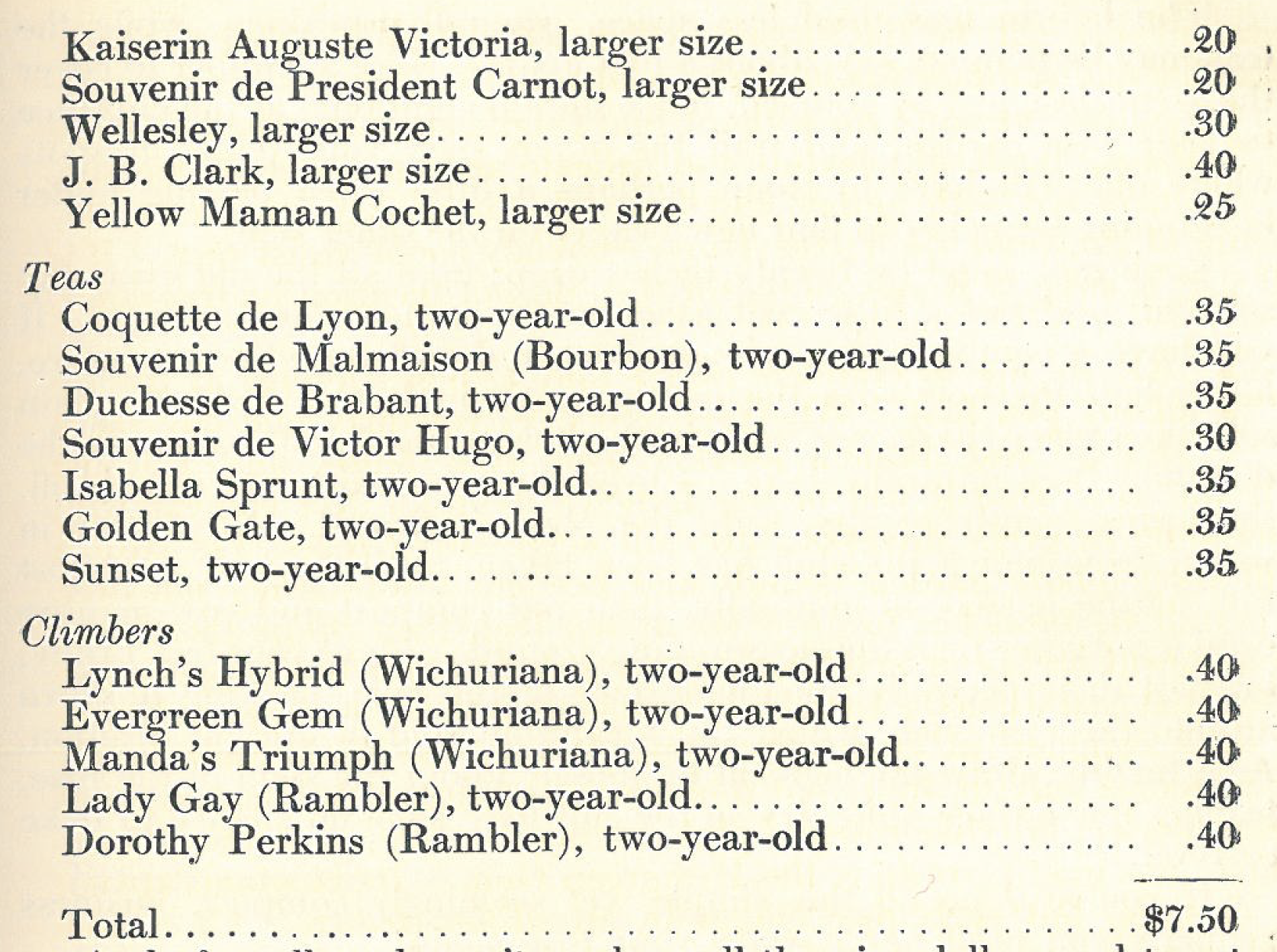

Ever since I was a little girl, I’ve hoped each spring some nice old uncle from India would send me fifty dollars accompanied by some gruesome threat, such as: “If you use one cent of this money for anything but roses, the first night the east wind blows a blackbird will come along and nip off your nose.” But as it hasn't really happened yet, I have to pretend along the last part of April or the first of May that it is about to happen and start to work to select the fifty dollars’ worth. It is so hard to advise another just which roses to get, because my list of irresistible ones grows each year, and then the rose-growers have been so generous sending me unlabeled gift roses it so happens now that some of my loveliest roses’ real names are unknown to me—they’ve had to attain names as best they might. For instance, that delicate pinky-white climber with the great loose clusters having the odor of frankincense and myrrh, is known to us as the "horse-bitten-rose," but to you that name would not be enlightening. Of course, we all have reminiscent reasons for wanting certain roses, and, if you are like me, you’ll keep on trying Marechal Niel and Fortune’s Yellow even though geography prohibits and zero browbeats you. One of my rose prides is the Cherokee which I have teased through three winters now, because of the great wild hedges I remember along the highways in the South. Each winter I lighten its protection, as I have a theory that if you can persuade a delicate rose to survive several Northern winters it grows hardier, following out Nature’s old law of adaptation to condition. Suppose we pretend together that the old uncle from India has stingily sent us only nine dollars and twenty-five cents instead of the expected fifty dollars, and make the best of it. Out of that amount we’ll have to get hybrid perpetuals, hybrid teas, plain teas and climbers—and feel thankful all at the same time. The hybrid perpetuals, you know, are the perfectly hardy roses, supposed only to bloom in June, though mine bloom spasmodically through the following months until winter. After each flowering I cut the branch that has flowered almost back to the original stalk, and then it puts out new shoots which often blossom. The hybrid teas have a hybrid perpetual ancestor on one side and will stand through a Northern winter with protection. They are perpetual joys, blooming constantly until November. We’ll have to have the hybrid teas even if we economize on the hybrid perpetuals. The teas—if you live in the North—are the roses you’ll keep on trying for sentimental reasons, association, or sheer bravado, because they are not hardy here. But they are the most florescent and are very beautiful, so we’ll have to indulge in a few for luxury and by getting two-year-old plants we will be generously rewarded this season anyway. The climbers we’ll purchase will be of the rambler and Wichuriana varieties. If we could have only one hybrid perpetual I’d beg for Gloire Lyonnaise. Its blossoms are sumptuously beautiful in form and of a golden white shade. The foliage is distinguished and it is unpopular with insects. Soleil d’Or is the most spectacular rose—a mingling of peach, marigold and flame. Given great richness of fare the bush will grow to prodigious size. A splendid velvety reddish black rose is the Prince Camille de Rohan. With Mrs. John Laing—that exquisite pink rose, we will have a white, a pink, a red and a yellow. If you know roses at all, and I said, "guess which hybrid tea I’ll mention first," I am sure you’d say "Killarney." Well, you would be right. It’s the Irish queen I’d be pining for first of all. In bud it is perfection; open, it "spreads and spreads till its heart lies bare." Even fallen, each petal is a poem—a deep pink shallop with prow of gold. Bessie Brown is so dignified, pallid and austere she is known as Elizabeth in my garden. The Kaiserin Auguste Victoria has a Teutonic hardiness and carries her cream-white flower head high and regally. Souvenir de President Carnot has a feminine-like blush, but a masculine vigor. The Wellesley gives us a delicious shade of pink. But here we have chosen two pinks and no red at all. How could I have forgotten that giant J. B. Clark, when he has grown nine feet in height trying to woo my Dorothy Perkins? He is the reddest, healthiest, tallest man-rose in my garden. For yellow we will choose the Maman Cochet. Now that we have reached the plain teas I’m glad to begin with one that has proved almost as hardy with me as a hybrid tea—that is, the Coquette de Lyon, which is a lemon yellow and positively wears itself out blooming. The Souvenir de Malmaison is strictly speaking a Bourbon, but we’ll let it be a tea for our purposes. It is so lovely with its shell pink tones, and we may be able to winter it, with especial care. Isabella Sprunt is another yellow rose of great florescence. It is so easy to get yellows in the teas, and yellow seems to go with frailness of constitution. But I’ve chosen only the ones that have proved hardiest with me, and those I can brag of having wintered a few times. For pure recklessness, let’s buy the Golden Gate, simply because we can’t resist its blending of pale gold and rose. Another extravagance will be the Sunset, which we will be satisfied to entertain this one summer for its topaz and ruby beauty. Of course, we can’t do without that fragile creature, the Duchesse de Brabant. Such silky texture and delicate pinkness of cheek has she. "Citron red with amber and fawn shading," say the rose catalogues of Souvenir de Victor Hugo—nobody could resist that. It is all that is sung of it and more, for they do not mention its fragrance. Here we are to climbers and I find Lynch’s hybrid at the tip of my pen first. Wherever you live, you may one day see a strange rose branch looking over your fence, and I’ll just tell you now, that it will be my Lynch’s hybrid. Not content with spreading in every direction, over all neighboring roses, I’m sure it will soon ignore garden bounds and become a wandering minstrel. I permit its branches to grow six or ten feet, then drape them over to adjacent arches or neighboring rose poles. This has happened so often that now when the Lynch’s hybrid blooms there are ropes and ropes of roses swinging in every direction. It is of the Wichuriana family and blooms only in June, but it blooms all of June. Its clusters are of many perfect fairylike roses of pink, paling to white. Of the Wichurianas my next favorite is the Evergreen Gem. Its blossoms are not in clusters, but each rose comes in an edition-de-luxe. Of a pale yellow with apricot tones, the color of the flower is enough to recommend it. But shut your eyes and whiff its perfume, and you’ll say "ripe apple." The Evergreen Gem prefers to sprawl on the ground and delights in covering stone terraces; it can be trained up, just as a monkey can be taught man tricks, but what’s the use? Manda’s Triumph (white) and Lady Gay (cherry pink) we must have. And I can’t resist ending with Dorothy Perkins, but to praise her well-known charms would use up needless type. I’ll only say, save all the cuttings of the Dorothy you plant, so you will have at least a thousand to comfort you when you’ve grown old. Now we’ll count up our list and put the roses down sensibly in line so we may see both what we have and what we have spent. And after all we haven’t used up all the nine dollars and twenty-five cents; so you may either change “larger size” to “Two-year-old,” or you may spend the surplus on that dream shatterer, the blue rose, which I see advertised on the back of the latest rose catalogue. It is worth considering in connection with our expenditures, that an ordinary bunch of roses you’d buy at the florist’s to send your sweetheart might cost more than all our miserly uncle has sent us, and the bouquet from the florist’s would be withered and thrown out in a week, while here we’re starting a rose garden for the grandchildren of that sweetheart to enjoy years and years from now. And so when we begin our rose garden we’ll begin it right—no superficial digging and sticking in any old way of these precious plants. First we’ll lay out our garden with a ball of twine tied to a stick, either informally or, improvising as we go, in some private original design which expresses us, not our neighbor. Then we will have it all dug as deep as we by strategy and beguilement can lure some man to dig. When it is all dug, then to mark out the individual holes, leaving generous space between the hybrid perpetuals because they grow to be such big fellows, and not forgetting to give Mr. J. B. Clark plenty of courting room. The hybrid teas need less space, generally speaking, while the teas may be planted, say, about a foot apart. Save a climber to cover the arch (designed by yourself, not a store bought one) at the entrance to your rose garden, and trail the others over your paths in spots where one will have to stoop perhaps a little when passing under blossoming branches to find new beauty on the other side. Each hole must be twenty inches deep; take all the old everyday soil out, and put a little coal ashes in the bottom for drainage. If you have a compost pile, mix compost and well-rotted cow-manure, filling half the hole with the mixture. Sprinkle this with the plain soil, then place the sacred bush in the hole, spreading the roots in the direction they naturally take. Cover the roots with more bed-soil, then press gently, gently, until the plant is firmed. Now pour in water, from which the chill has been taken, until the hole is almost full, letting it soak in gradually, then put compost and cow-manure until it is higher than the surrounding ground. Plant your feet firmly, but not disrespectfully, on the surface of the hole, packing it down around the rose-bush, which you meantime hold in upright position. As a finality, draw the bed-soil up loosely about the stem of the rose, leaving the surface quite dry so the sun may have no chance to bake or broil. If you have done all this simple, yet seemingly complex, business properly you need never water your rose again! When the bushes reach the blooming stage, trim back severely the branches which have flowered, always trimming so as to leave an eye on the outside of the branch. Don't be afraid of cutting too much. The courageous rose-surgeon is the one who gets the largest fees in flowers. If you have done enough trimming through the summer blooming months, there will be no necessity for any trimming in the fall, except always to cut out dead branches. Then, too, when you think of the cold that’s coming, and the struggle the poor things will have to go through during the winter, to trim them at this perilous time would be as mean as to strike a man when he’s down. In mid-April, prune all blackened ends and weak branches. Some of your hybrid teas may look absolutely dead, but don’t give them up yet. Trim the bushes down to within two inches of the ground, and shortly you will be rejoiced to see red-nosed sprouts peeping through the ground—shoots from the roots, which generally survive. If you don’t own a compost pile begin one now. Even a weed becomes valuable when pulled up and thrown on the compost. Contribute all dead blossoms, weedings, trimmings, garden rubbish, leaves, manure rakings and even some garbage and dish-water. Place the compost far enough from the house so you won’t bother about the sanitary problem, and every few weeks spade a few shovelfuls of earth over the whole pile. After a year’s mellowing you will have something more valuable than manure to work into your rose beds. Dig continually with pronged spade about your roses, being careful not to tear the roots. The soil should always be kept loose if you would be spared the bugbear of watering. Mulch with lawn clippings, spading old supply under when the fresh is ready. Spray once a week with a water made foamy by tobacco and sulphur soap. You will not vanquish the insects—no, not in this world, but even abating them is a human triumph. About the middle of November purchase rye straw by the bundle and after tying your rose-bushes gently to a firm stake, sheathe the straw about the hybrid teas and plain teas not too tightly, tying in about three places. The hybrid perpetuals may go nude all winter. A trip to the West Indies or Sicily about the middle of March might help you to overcome the unconquerable temptation of uncovering your roses too soon. Returning from your voyage about the second week in April, the plants could be disrobed safely, and—live happily ever after, or at least all summer. You will realize, of course, that growing roses is not easy work. Believe me, the rose-grower can be neither a fool nor a lazy man. It’s so hard to write plain, practical facts about roses. To write of them properly one would irresistibly compose a sonnet. And when you pick your first great basketful some very dewy June morning, please place them in an old blue bowl for my sake, and the sake of our Indian uncle, whom we had almost forgotten. |